In late 1970 I hounded the bosses at United Press International (UPI) to send me to Vietnam to cover the fighting. The opportunity was slipping away as the U.S. withdrew its troops and transferred the responsibility of conducting the war to the government of South Vietnam. As a young news photographer this was the biggest American story of my generation, the kind I lived to tell, and I didn’t want to miss it.

In January of 1971 UPI finally agreed to transfer me to Saigon. I was going to replace Kent Potter who had been covering Vietnam for three years. Potter and I were the same age, 23. I was really excited about finally being able to get to the action. Although several photographers had died there over the years, I hadn’t let that bother me, until two weeks later on February 10, when four photographers were shot down in a helicopter over Laos and were killed. A personal hero of mine Larry Burrows of LIFE, Henri Huet of AP, Keisaburo Shimamoto of Newsweek, and UPI’s Kent Potter who was supposed to switch out with me. Although I didn’t know Potter it freaked me out to think of stepping into his job under these circumstances. What was I doing? This was seeming totally nuts and even more dangerous all of a sudden. I started to have grave second thoughts, but the idea of changing my mind and not going seemed like an even worse option. I also didn’t want to look back years later and regret not doing it, an even scarier thought.

The next few weeks turned into one big going away bash. It seemed like I and everyone else thought this was going to be a one-way trip, so the theme became, Let’s Party!

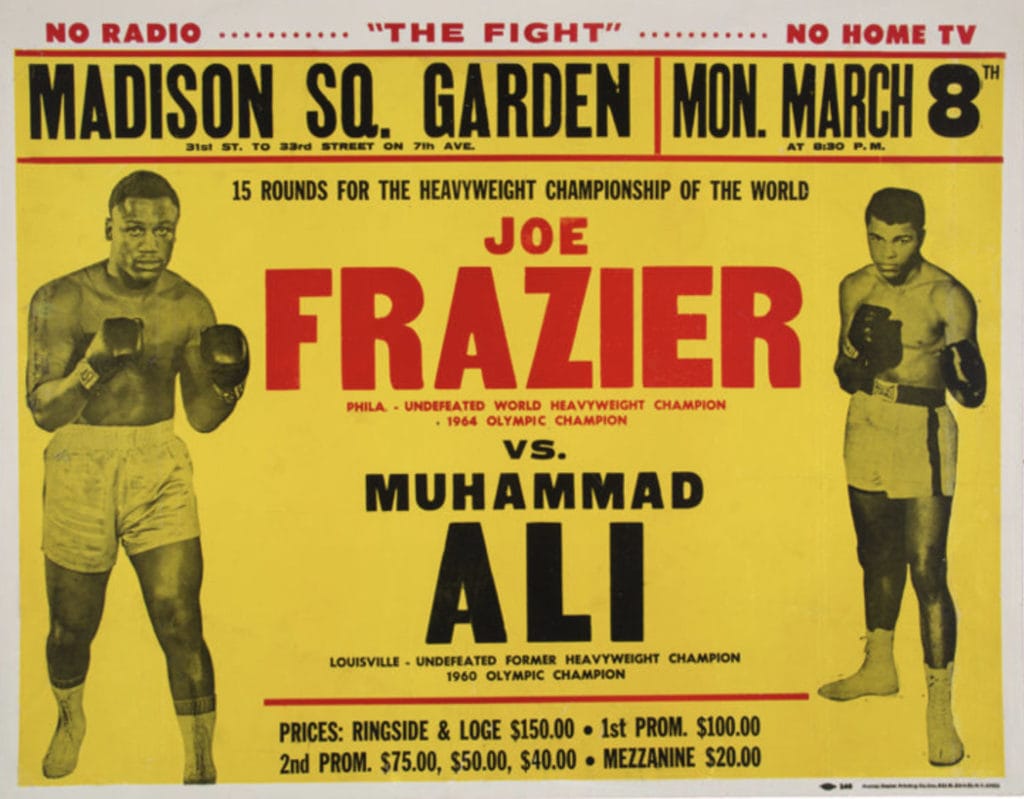

As a parting gift to me, or perhaps a guilty farewell present because they knew I was going off to my death, the UPI brass offered me a coveted assignment. A ringside position at the Ali-Frazier “Fight of the Century” at Madison Square Garden in New York on March 8th. It was my last domestic job before shipping out to Vietnam.

When fight day arrived I was totally fatigued from too much booze, cigarettes, and fun . . . The afternoon of the fight I could barely move. I was staying at friend and mentor Dirck Halstead’s place in NYC. As I was preparing to drag myself out the door to go the fight he took one look at me and said, “Jesus Kennerly, you look like shit, here, take this pill.” I had no idea what it was, but I definitely needed something.

By the time I got to the Garden I was on fire. My eyes were wide, my reflexes cat-like. The spiderwebs had been exorcised from my brain. Bring ’em on, I couldn’t wait for the main event.

I was squeezed in between three other photographers as we all leaned over the apron of the ring trying to shoot under the ropes. Turned out I couldn’t miss. In the fifth round I froze Frazier as he drove a right hook into Ali’s head that ricocheted off his face. It happened in a nanosecond. Ali’s expression was contorted by the force of the blow.

As the fight culminated in the 15th and final round it appeared that Frazier was ahead.

Smokin’ Joe sealed the deal with a lightning-fast left hook that knocked Ali off his feet. This video shows just how fast it all happened.

I caught The Greatest as he headed down. In my head it was slow motion, in reality it was a fraction of a second, and I nailed it.

The final bell rang, and Frazier raised his gloved hand in victory right above me. After the fight, Larry DeSantis, UPI’s chief editor, congratulated me on my coverage.

I woke up the next morning to see my Ali knockdown photo on the front of the New York Times. It was also my 24th birthday. I also scored the front of the New York Daily News with my image of Frazier landing the right to Ali’s head. Being published on page one of both those papers when they had several of their own photogs at the event was unprecedented, and my colleagues most likely weren’t happy about it. I was probably going to be safer in Vietnam! That photo of Ali falling also became part of my Pulitzer portfolio for the work I did in 1971. It included photos from the Vietnam War, Cambodia combat, and refugees pouring into India from East Pakistan.

The only other person who caught that decisive moment was Elliot Erwitt who was up in the stands shooting for Magnum.

His wide shot must have been taken within a millisecond of mine, because it happened so fast and ended almost as soon as it started. I am in Elliott’s frame, second from left of the four photographers on the apron in the foreground as Ali goes down.

The day after the fight I asked Dirck what the hell he gave me. “That was a purple heart,” he said. (Further research revealed that the tag came from the pill’s triangular shape and blue color. Officially it was Dexamyl, a mood elevator that was an amphetamine/barbiturate combo). First and last time I took one of those, but who knows what would have happened otherwise. One thing’s certain, and this can be corroborated by family and friends, I usually produce plenty of my own energy, and that’s normally how I fly!