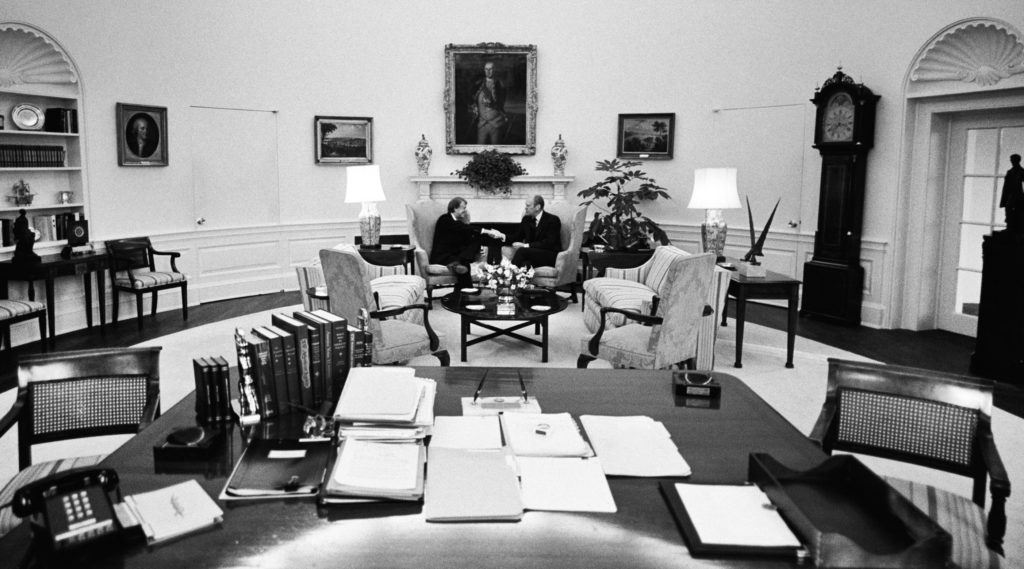

President Gerald R. Ford held his first meeting with President-elect Jimmy Carter on November 22, 1976, thirteen years to the day after President John F. Kennedy was assassinated. It was the first time Carter had been in the White House.

The two sat in the Oval Office under the portrait of George Washington that hangs over the fireplace. After the press “photo op” they were alone. I was behind the president’s desk looking for an angle when President Ford unexpectedly reached out and shook hands with Carter, saying, “I’m sorry, but I haven’t formally congratulated you on winning the election.” It was a spontaneous moment not for the public benefit, but a genuine signal of respect. My wide angle frame of that gesture featured the desk in the foreground, covered with papers. On the other side of that historic room, the man who would be president shook hands with the man who was. In my mind it showed the vastness of the job with mere mortals in temporary custody of its powers.

President Ford had conceded to Carter the morning after the election, and pledged a smooth transition. Ford’s chief of staff Dick Cheney led the effort for the president, and Jack Watson for Carter. Ford told Cheney to take the lead in the process, and that’s what he did. Ford’s cooperation even went back to before Carter was elected. Right after he was nominated at the Democratic convention in New York, the president directed that Carter be given highly classified intelligence briefings so he would be more prepared if he won the election. To show his seriousness about it, the president had the head of the CIA, George H.W. Bush, personally brief Carter at his home in Plains, Georgia.

By the time Carter got to the White House for his initial visit, three weeks had elapsed since the election, but the transition was fully underway. The two met privately, and discussed every element of the job, particularly what was happening in the area of national security. Cheney and Watson, along with Counsellor Jack Marsh, talked in the Cabinet Room before joining the oval office meeting. The president and Carter went through binders filled with material that had been provided by the Ford team. They talked about everything from family to foreign leaders.

As their meeting ended, President Ford told President-elect Carter that he wanted to show him something. They went to his private “hideway” right next to the oval office. Ford’s personal secretary Dorthey Downton was there. President Ford made a from-the-heart offer. He said, “Jimmy, I’d like you to have this office during the transition if you want.” He told the president-elect that he would be available to him anytime. Carter seemed taken aback at the proposal. Ms. Downtown, on the other hand, appeared to regard Carter as if he had just landed from Mars. Like many of us, this wasn’t a visit she had been welcoming. As magnanimous as was the proposition to take over his private office, neither Cheney or Watson thought it was a good idea, and apparently not the president-elect either. He didn’t want to muddy the waters as to whom was in charge until he took over, and he spent most of his transition time back home in Plains.

When the two leaders walked out of their meeting to greet the press, President-elect Carter told them, “There cannot have been a better demonstration of unity and friendship and good will than there has been shown to me by President Ford since the election. I believe that this year’s debates and the election itself has reached a conclusion which leaves our country unified, and I have expressed many times in the last few weeks my deep appreciation to President Ford for the gracious way in which he has welcomed me.”

President Ford responded by saying that he had, “re‐emphasized to Governor Carter that my administration would cooperate 100 percent in making certain that the transition would he carried out in the best interest of the American people.”

When they finished talking to reporters after their meeting, President-elect Carter turned to President Ford before walking to his car and said, “God bless you.”

On his final half-day in the White House on January 20, 1977, President Ford was particularly anxious to thank the White House Residence staff for all they had done for him and his family in the two and a half years that they occupied 1600 Pennsylvania Ave. He popped into the kitchen to say goodbye, searched the hallways to make sure he didn’t miss anyone, and bid a final farewell to one of his favorite staffers underneath a portrait of Abraham Lincoln in the State Dining Room. It was emotional for all of us.

Later that morning the Fords greeted the Carters as they arrived at the White House for what has become a traditional rite, a pre-Inaugural coffee in the Blue Room of the Executive Mansion. I caught a glance of Carter looking at Ford with an expression that seemed somewhere between awe and, “what have I gotten myself into?” It was a friendly gathering, considering the circumstances. The two leaders had a quiet and private moment, a portrait of George Washington between them. I felt the history.

President Ford wanted a group photo of everyone, and assembled Vice President and Mrs. Nelson Rockefeller, and Vice President-elect and Mrs. Walter Mondale. If you didn’t know what was happening it looked like a group of old friends, not the heads of the incoming and outgoing administrations.

Then it was time for the Fords and Carters to take that short journey up Pennsylvania Avenue to the U.S. Capitol for the Inauguration. Only three outgoing presidents, John Adams in 1801, John Quincy Adams in 1829, and Andrew Johnson in 1869, refused to take that ride to attend their successors’ inaugurations. No doubt Donald Trump will become the fourth 152 years later. Trump also has impeachment in common with Johnson, so they would have had a lot to talk about if they’d been sharing a carriage. John Adams, who passed on attending Thomas Jefferson’s inauguration, did speak words that Trump should have heeded: “Facts are stubborn things; and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictates of our passions, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence.” Hmmm. Did he perhaps foresee the fraud-free 2020 election?

Carter remembered that trip to the Hill many years later as, “an uncomfortable ride.” The picture bears it out. Because there was no room for me to squeeze into the limo, I mounted a camera between Speaker of the House Tip O’Neill, and Sen. Howard Cannon of the Inaugural Arrangements Committee. I strung the shutter release cable to the front where the Secret Service agent riding shotgun agreed to take the pictures. Before the motorcade left the North Portico of the White House, I told the substantially-sized Speaker to lean over to his left so he wouldn’t block the shot. He happily obliged. Afterwards the agent told me that he didn’t think the photos would be that good because, “the two of them didn’t say much.” He was wrong about the image. As the old cliché goes, the picture told the story.

Although I would have preferred seeing my boss President Ford being sworn-in, not Jimmy Carter, it was the kind of moment that I live to document. I was witnessing what our country represents. A peaceful and honorable transfer of power. One where everybody pulls together. An American tradition. A Democratic staple of our free society. We’ve been doing it since George Washington turned over the reins of power to John Adams in 1797.

For the first time in our country’s history, this year we are not doing it the right way.

Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona: David Hume Kennerly Archive.

© Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents