The big announcement in the spring of 1972 came via a telex message to the United Press International office in Saigon where I was the photo bureau chief. It read: “01170 Saigon-Kennerly has won Pulitzer for Feature Photography, which brings congrats from all here. Now need effort some quotes from him and pinpoint his location when advised for sidebar story, Brannan/NXCables.”

I didn’t believe it. How could I have won my profession’s highest award and not even known I had been entered? I thought it was a mistake or, worse, a prank. Bert Okuley, the news chief at the Saigon bureau, fired back a note. “EXHSG Brannan’s 01170. Are you kidding? If so it isn’t much of a joke. Is there a Pulitzer awarded to a UNIPRESS photographer, and is it Kennerly? Okuley”

Then the wire machine broke down. It wasn’t possible in those days just to pick up the phone and call the states. For three hours we were cut off from the world. Without warning the telex sprung back to life, and a torrent of messages flooded forth. The first said, “01181 Okuley’s 02054 No kidding and can you reach Kennerly for sudden comment need to know where he was when he got the news, Wood/NXCables”

My favorite cable was from my Associated Press competitor Eddie Adams who won a Pulitzer for his famous photo of the chief of the Vietnamese National Police shooting a Viet Cong suspect in the head. Before I left for Southeast Asia Eddie told me that I was wasting my time, and rather immodestly suggested that, “All the good photos in Vietnam had been taken.” His message to me after I won simply said,

“I was wrong. Congratulations. Eddie.”

So, no joke, I had just joined the Pulitzer Club.

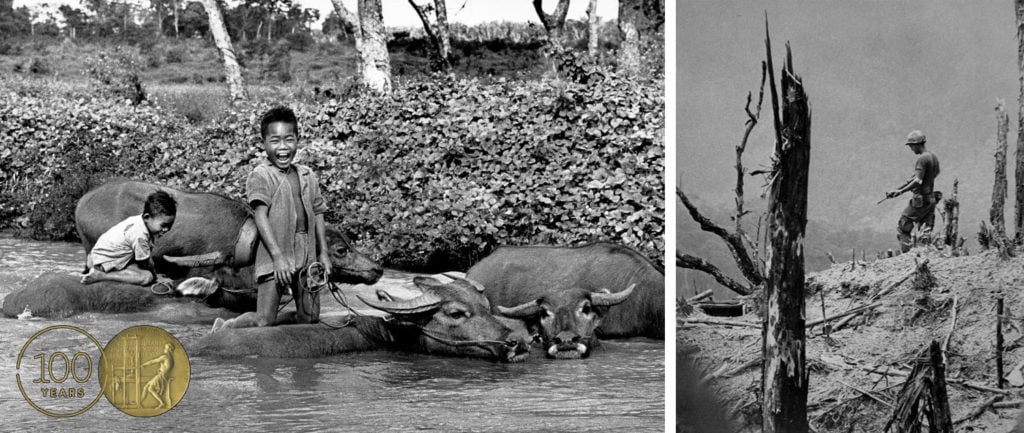

Weeks later I saw the official citation: “For an outstanding example of feature photography, awarded to David Hume Kennerly of United Press International for his dramatic pictures of the Vietnam War in 1971.” It also noted that, “he specializes in pictures that capture the loneliness and desolation of war.” The representative photo from the portfolio, (not knowing a portfolio was entered, I had no idea what was in it), was a photo that I had taken of an American soldier walking across a shattered hillside near the A Shau Valley up in the mountains outside of Hue. It definitely fit the lonely, desolate, and dangerous bill.

What I found out later is that Larry DeSantis, chief photo editor for UPI, and a man whose laser-guided criticism had helped to make me a better photographer, had submitted me for the Pulitzer. During 1971, as photos of mine that he liked came across his desk, Larry would toss copies into the drawer. At the end of the year he scooped them up and entered them in the contest, underscoring how we can’t always make it on our own, but need some help and faith from others along the way. Larry’s gone now, but before he left I had the chance to tell him that he was the greatest photo editor on earth. I also told him that it was our award, not just mine.

Years later I visited the Pulitzer archive at Columbia University in New York to see for myself what pictures had won. I discovered that my portfolio contained eleven photographs. Included was a single color photo taken at a little firebase named LZ Lonely that was similar to a black and white picture of the same situation, and to my knowledge is the first color photo that was part of a winning Pulitzer entry. To my surprise there was also a photo from the Ali-Frazier, “Fight of the Century,” in Madison Square Garden taken on March 8, 1971. That picture, in the 15th round of the world heavyweight title bout, showed Mohammad Ali in mid air falling to the canvas after being walloped by a vicious Joe Frazier left hook. The fight was my last domestic assignment before I left to cover the war in Vietnam, and that picture appeared on dozens of front pages around the world the next day, including the New York Times, (that also happened to be my 24th birthday). The other photos were from Vietnam, Cambodia, and of refugees in India who had escaped from East Pakistan. It was a wide and inclusive array of my year in pictures.

The Feature Photography prize debuted in 1968 when the Pulitzer board split photography into two categories, Feature and Spot News. Spot News became Breaking News in 2000. The Feature category was created for a single photo, essays, or in my case a portfolio of pictures taken during a calendar year. The award was principally designed for professional photographers.

The first winner in the Feature category was my late friend and colleague Toshio Sakai who won for Vietnam coverage in 1968. The Spot/Breaking News category has contained some astonishing and memorable images over the years. Three of the best ever are Joe Rosenthal’s Marines raising the flag atop Mount Surabachi on Iwo Jima, Nick Ut’s napalmed Vietnamese girl running down the road, and of course Eddie’s Saigon execution photo. I was happy and honored to join the ranks of these great photographers.

But that isn’t the end of the saga of my Pulitzer-winning pictures. The rest of it illustrates how valuable, and in many cases vulnerable, photography can be.

All the images I made for UPI resided in their files. Somehow the original negative for the GI traversing the devastated hill went missing, and was never found. To this day I don’t have an original print of that photo, but fortunately have an excellent copy from a print made at the time.

A common practice at UPI was to cut the strip of 36 black and white negatives into sections of three frames each, usually keeping the selected image in the middle with a photo on each side. That was done to allow the more modern 35mm film to fit into yellow envelopes that were designed to accommodate the 4 x 5-inch negatives shot during an earlier era. Astonishingly UPI chucked the other negatives. In other words 90 percent or more of the images I shot during my five years as a UPI photographer were discarded, including at least a year and a half’s worth of Vietnam pictures. It was heartbreaking.

Photojournalism is a hybrid form. Early news photography was used mainly to illustrate the written stories. Pictures were not always seen as news documents in their own right. For decades, bulky negatives and prints were disposed of in stunning quantities. To cite just one example, several years of photographs of events covered by The Washington Post’s excellent photographers, including classic images from the Watergate hearings and the White House, were trashed by a zealous bean counter. To save space.

This year, I’ve embarked on a mission to prevent that from happening to me. I hope to collect, preserve and scan my entire collection. For 12 years, my wife Rebecca and I have been pulling together and organizing everything I have shot, written and collected, during my 50-year career as a professional photographer, (and the archive continues to grow, I’m still out there shooting!).

The images I’ve made are not just pictures to me. Each one represents a sliver of my soul. I’ve seen joy and sorrow, horror and heroism, triumph and defeat. I have witnessed and documented the human experience at its worst and best. It has been my mission to tell those stories. The pictures I took in 1971 that won the ’72 Pulitzer were deeply meaningful to me. They encompassed a galaxy of human emotions and conditions. It’s hard to imagine that I was in four different war zones that year. Sure, it took a personal toll, but nothing like the price the participants pay, particularly innocent children and civilians. I do it for them.

I will always be grateful to the Pulitzer committee for selecting my work as worthy of our profession’s highest honor. It not only acknowledged me, but all of the other photographers from conflicts past and present. Many of them died in pursuit of showing the truth of what war is really about. I will never forget them, and the impact they made on the world.