Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona: David Hume Kennerly Archive.

© Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents

In early 1971 United Press International assigned me to their Saigon bureau to replace photographer Kent Potter who was rotating out. On Feb. 10, 1971, Potter and three other photographers perished when their chopper was shot down over Laos during the Lam Son 719 operation. Larry Burrows of Life, Henri Huet of the AP, and Keisaburo Shimamoto of Newsweek were among those who died. I don’t know any of those great photographers, but Burrows was a personal hero, and his photos inspired my desire to cover the war. A few weeks later, and shortly after I turned 24, I was on a plane bound for Saigon.

I spent over two years photographing combat in Indochina, and In 1972, I was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for my previous year’s work in Vietnam, Cambodia, and India where I photographed refugees escaping across the border from East Pakistan.

Vietnam became part of my DNA, and everything that has happened to me since has been informed by that experience. I was 24, and my first year as a combat photographer was so intense, and there were so many close calls, I never figured to see 25. When I celebrated that birthday in Saigon, I felt that every one after was a bonus. So far that windfall has added up to an extra 43 years! I have tried to use them well.

I returned to the states in mid-1973 to go to work for TIME Magazine. One of my early assignments was the Watergate melee, and I was also assigned to photograph House Minority Leader Gerald R. Ford after Vice President Agnew resigned in the fall of that year. A portrait that I took of Ford ran on the cover of TIME when President Nixon announced that he would replace Agnew as the new vice president. TIME then assigned me to cover Ford full-time. When President Nixon resigned, and Ford replaced him, he asked me to be his chief photographer. With that job came total access, not just to the President and his family, but to everything that was going on behind the scenes. It was quite an honor, wildly exciting, and one of the most professionally and personally rewarding times of my life.

On March 3, 1975, six months into the Ford Presidency, South Vietnam began to unravel when the North Vietnamese Army attacked the Central Highlands city of Ban Me Thuot. After a few days of heavy fighting that saw thousands of casualties, particularly among the civilian population, that key city fell to the North Vietnamese. This was the beginning of the end for South Vietnam.

My previous life as a combat shooter was running head-on into my latest career as a presidential photographer. I documented the events of the next few weeks as any professional news photographer would, but with a major exception. I was deep inside the White House as the president’s photographer, and was given an unparalleled opportunity to see a war implode from within the halls of power. This special access also led to a secret trip back to Vietnam on a special mission for the President of the United States, and then back to the White House for the finale of the Vietnam drama.

April 28 and 29th of 1975 were personal days of hell as the last act of the Vietnam tragedy unfolded. I didn’t sleep, and was consumed with making sure that I photographed every minute that I could of these tense final days. I was uniquely qualified to record this series of events, but I was also emotionally drained by the circumstances. During the war itself I played through my pain to document the story, and I did the same during those final days. I always knew that just a handful of people with tremendous power made the decisions that shaped our lives. They were the ones who started and ended wars. As someone who had always been an outsider it was startling to see that process in action. Just a few short years earlier, I was consumed with a drive to document events from the other end – and to be out on the front lines where the action was. Or so I thought. Not much later, I found myself in the center of action of another kind – watching and recording the agony of decisions about life, death and the future of nations being made one at a time by a president until there were no more decisions to make. And then, the Vietnam War was over.

This is my account and photos of the final days of Vietnam. Direct quotes from the participants are from declassified minutes of National Security Council meetings, Memorandums of Conversations, Cabinet meetings, White House press conferences, President Ford’s book, “A Time to Heal,” Donald Rumsfeld’s book “Known and Unknown,” and my autobiography, “Shooter.”

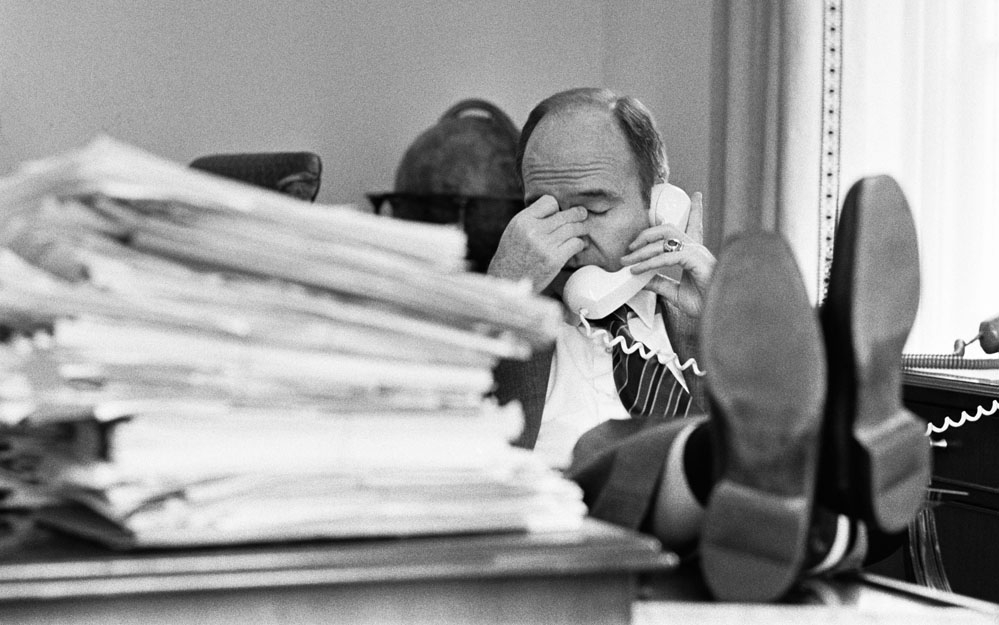

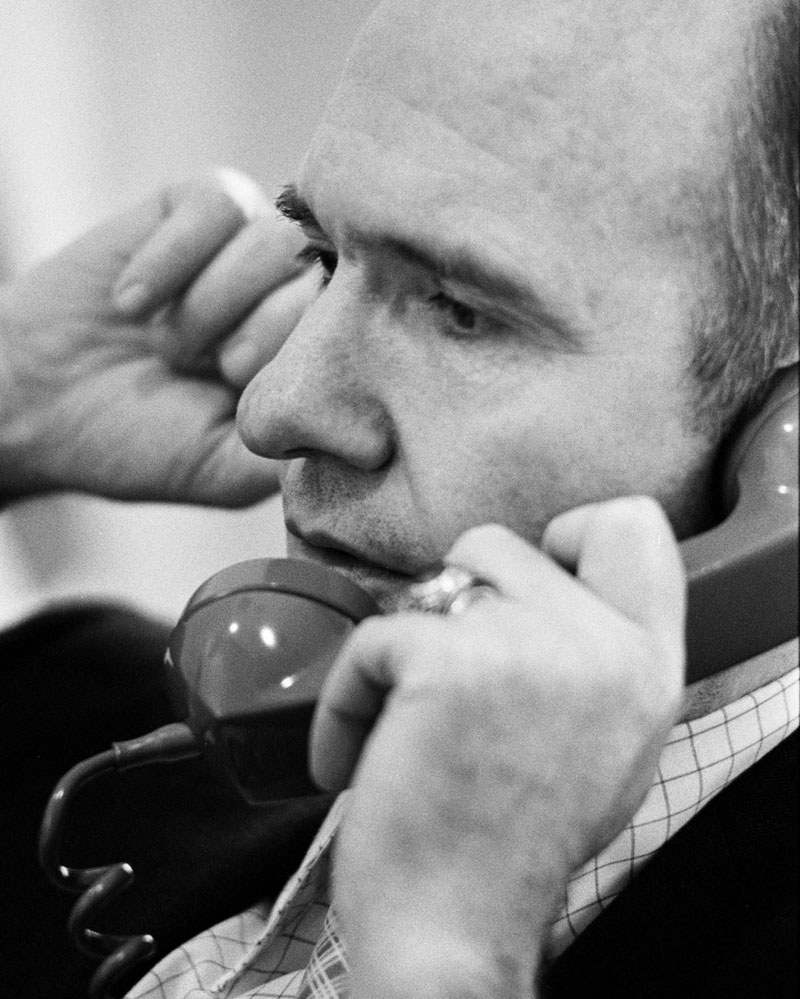

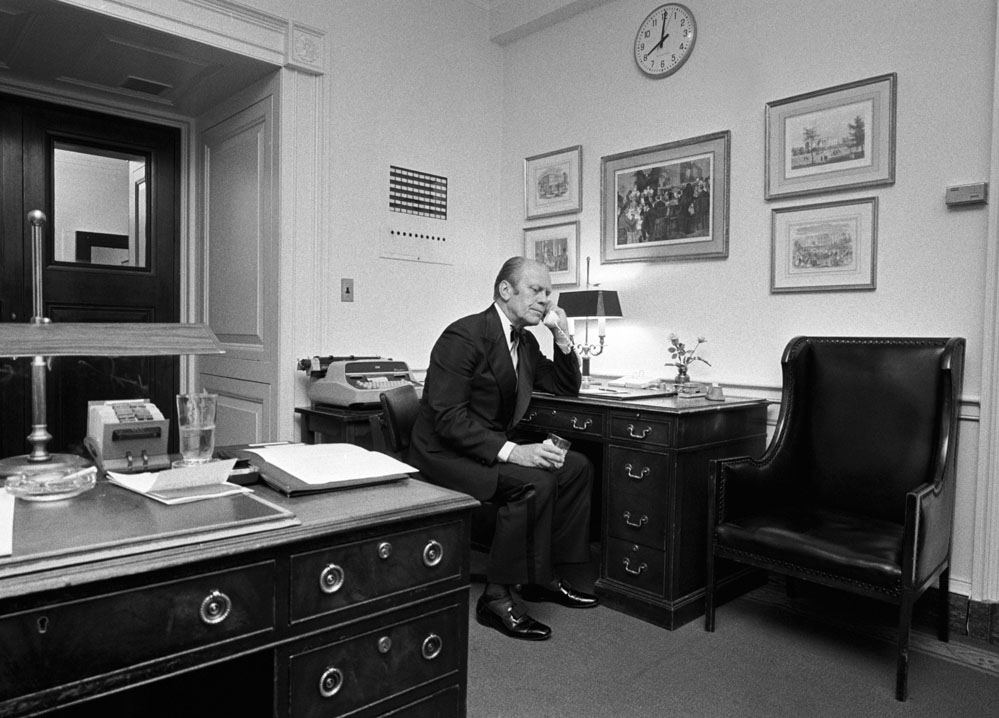

The North Vietnamese were now in Hue, and moving on Da Nang. It looked as if all of the northern provinces of S. Vietnam would fall to the advancing Communist forces. On March 25th President Ford met in the oval office with U.S. Army Chief of Staff General Frederick Weyand and U.S. Ambassador to S. Vietnam Graham Martin. The president discussed dispatching the general on a fact-finding mission to Saigon to see if anything could be done to stem the advancing North Vietnamese tide. Gen. Weyand had heroically served several tours in Vietnam and knew the intricacies of the conflict. The president felt confident he would give him the best assessment of the situation. Secretary of State and National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger, and his deputy Gen. Brent Scowcroft participated in the meeting also. The photo I took of Deputy National Security Advisor Gen. Brent Scowcroft on March 16 in his White House office as he talked on the phone to a colleague reflected the gravity of the situation.

WASHINGTON -- MAR 16: Deputy National Security Advisor Gen. Brent Scowcroft in his White House office reacts to the news that the South Vietnamese town of Ban Me Thuot has fallen to the North Vietnamese, March 16, 1975, Washington D.C. Ban Me Thout was a decisive battle of the Vietnam War and led to the complete destruction of South Vietnam's II Corps Tactical Zone and exposed the incredible weaknesses in the South Vietnamese Army. This was the beginning of the end of South Vietnam. The defeat at Ban Me Thuot and the disastrous evacuation from the Central Highlands came about as a result of two major mistakes. In the days leading up to the assault, the S. Vietnamese high command ignored intelligence which showed the presence of several North Vietnamese combat divisions around the district, and then President Nguyen Van Thieu's strategy to withdraw from the Central Highlands was poorly planned and implemented, resulting in a civilian catastrophe.

The president told Gen. Weyand, “Fred, you are going with the ambassador. This is one of the most significant missions you ever had. You are not going over there to lose, but to be tough and see what we can do.” The president continued, “We want your recommendation for the things which can be tough and shocking to the North. I regret I don’t have the authority to do some of the things President Nixon could do.” (These quotes are taken from recently declassified notes of that meeting). Secretary Kissinger asked, “What is the real situation and why? What can be done?” Weyand replied, “We will bring back a general appraisal and give them a shot in the arm.”

WASHINGTON -- MAR 25: (9:22-10:25 a.m.) President Gerald R. Ford talks to U.S. Ambassador to South Vietnam Graham Martin, Army Chief of Staff Gen. Frederick Weyand, and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger in the Oval Office the White House. March 25, 1975. President Ford dispatched Gen. Weyand on a mission to Vietnam to see if anything could be done to help the South Vietnamese government stem the tide of the advancing North Vietnamese Communists. Ambassador Martin, who was in the states for a medical problem, would return to Saigon with Weyand.

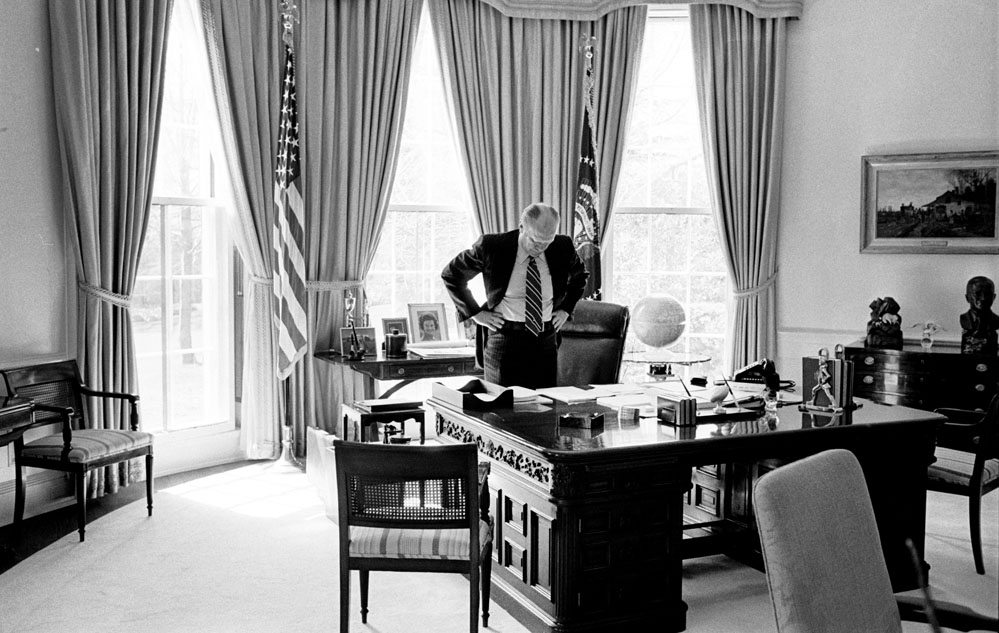

After they left I took this photo of the president alone in the office, clearly frustrated. We talked about the trip, and I told him that, because of my extensive experience in Vietnam, I would like to go with Weyand. The president agreed, and said that he would depend on me to deliver to him my usual impartial and candid point of view when I got back.

WASHINGTON -- MAR 25: (9:22-10:25 a.m.) President Gerald R. Ford walks to the door with (L-R) Deputy National Security Advisor Brent Scowcroft, U.S. Ambassador to South Vietnam Graham Martin, Army Chief of Staff Gen. Frederick Weyand, and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger in the Oval Office the White House. March 25, 1975. President Ford dispatched Gen. Weyand on a mission to Vietnam to see if anything could be done to halt the advancing North Vietnamese Communists. Amb. Martin would fly with him.

My office was on the ground floor of the White House, and I dropped in to tell my staff that I was leaving early on a trip the next day. I hung a sign on my door that said, “Gone to Vietnam. Back in two weeks.” My staff thought I was joking until I didn’t turn up the next day, or for almost two weeks. Later that evening I went to say goodbye to the Fords and asked the president for a loan. These were the pre ATM days. “The banks are closed, and I’ll be gone before they open, “ I said. President Ford pulled all the bills that he had in his wallet. “Here’s forty seven dollars,” he said. “Don’t spend it all at once!”, Then he turned serious, put his arm around my shoulder, and said, “be careful.”

WASHINGTON -- MAR 25: (10:30 a.m.) President Gerald R. Ford after meeting with Deputy National Security Advisor Brent Scowcroft, U.S. Ambassador to South Vietnam Graham Martin, Army Chief of Staff Gen. Frederick Weyand, Ford, and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger in the Oval Office the White House. March 25, 1975. President Ford dispatched Gen. Weyand and Amb. Martin on a mission to Vietnam to see if anything could be done to stop the advancing North Vietnamese Communists.

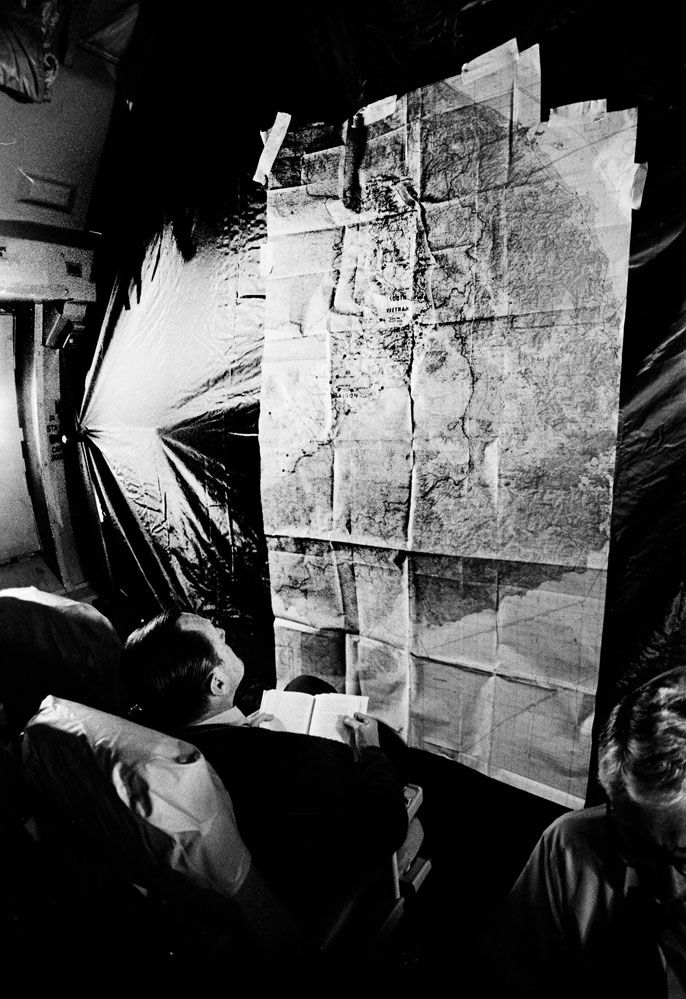

General Weyand’s plane, an Air Force C-141, made two refueling stops in Anchorage and Tokyo before reaching Saigon 24 hours later. I got to know Ken Quinn on board the plane, a young National Security Council staffer who specialized in Southeast Asia. I also spent time on the trip, and there was plenty of it, talking to George Carver and Ted Shackley, two senior CIA officials. They were men who worked in the deep shadows, and were major players in the Vietnam saga. Once in Vietnam, Ken Quinn and I were assigned to be roommates at Ambassador Martin’s residence in Saigon. At that time, there was no official evacuation of Vietnamese underway. However, Ken and his buddies knew that the end was in sight. I discovered that Ken and some fellow NSC staffers were running an effective, vast and very unofficial underground network that was spiriting thousands of Vietnamese allies out of the country and to safety. At the same time, the American news organizations were frantic about the safety of their Vietnamese employees and dependents. I arranged an off the record meeting with the ambassador and Art Lord who represented the media that resulted in an unofficial process to start getting some of those individuals out of the country. The ambassador thought some of these news organizations were hypocritical because while they were asking for help to get their own people to safety, they were reporting that there would be no reprisals against the southern Vietnamese if the northerners took over. The downside wasn't an exaggeration, and many southerners who were still trapped after the fall of Saigon were subject to severe reprisals.

OVER THE PACIFIC -- MAR 26: U.S. Army Chief of Staff Gen. Frederick Weyand looks at a map of Vietnam as he heads to that war torn country on a special mission for the President of the United States aboard a U.S. Air Force C-141, March 26, 1975. SAIGON -- MAR 27: U.S. Army Chief of Staff Gen. Frederick Weyand talks to U.S. Ambassador Graham Martin shortly before landing in Saigon aboard a U.S. Air Force C-5A. Weyand was on a special mission for President Gerald R. Ford to give recommendations on how to save S. Vietnam from the advancing North Vietnamese Army. Saigon, Vietnam, March 27, 1975.

SAIGON -- MAR 27: A pensive U.S. Ambassador to Vietnam Graham Martin shortly before landing in Saigon aboard a U.S. Air Force C-5A. In the background is Army Chief of Staff Gen. Frederick Weyand. Saigon, Vietnam, March 27, 1975.

I was not part of Gen. Weyand’s official briefings, but at the same time I had a very personal directive from the president to give him my private assessment of the situation. After a day in Saigon I decided to head up north. Da Nang was out of the question as it was effectively in North Vietnamese control, so I made my way to Nha Trang, a small city 300 miles south of Da Nang that was already overrun with refugees. When I arrived, I found Montcrieff Spear, the U.S. Consul General in Nha Trang, preparing to leave. His wife was actually packing when I arrived. However, before he could go, he needed to find his colleague and fellow consul general Al Francis who had escaped from Da Nang.

Spear and I took an Air America chopper up to Cam Ranh Bay to search for Al Francis who had managed to flee from Da Nang on a ship that had been hijacked by fleeing South Vietnamese troops. We saw a large vessel crammed with thousands of troops, and at least one of them, in frustration at the situation I guess, fired at our American-flagged chopper. They missed, but caused the pilot to make one helluva U-turn. That story also made AP, and was seen by my parents who didn’t know I was back in Vietnam (it was, after all, a secret mission). They called the White House, and were surprised that they were put right through to the president himself (the operators there knew me well!). He had just been briefed on the incident, and told them I was just fine, but still overly adventurous.

CAM RANH BAY -- MAR 30: The Pioneer Commander, a U.S. ship carries thousands of Vietnamese soldiers who had hijacked the vessel from Da Nang in front of the advancing Communists, pulls into Cam Ranh Bay, South Vietnam, March 30, 1975. This photo was taken from a U.S. helicopter by President Gerald R. Ford's official White House photographer David Hume Kennerly who was on a mission from the president to document the deteriorating situation, and to report back directly to him with his account. The frustrated fleeing troops fired on Kennerly’s chopper, but neither he or the U.S. Consul General Montcrieff Spear who was also aboard were hit.

Al Francis had made it onto a tugboat from the big ship, and that’s where we spotted him. He waved as we flew over, and we landed in Cam Ranh Bay to pick him up before he and his Spear headed back to Saigon. Nha Trang was abandoned that day, and I made a detour over to Phnom Penh.

CAM RANH BAY -- MAR 30: U.S. Consul Al Francis waves from a tugboat after escaping from Da Nang in front of the advancing Communists, March 30, 1975, Cam Ranh Bay, South Vietnam. Francis was the U.S. Consul to DaNang, and boarded a ship there that had been taken over by fleeing S. Vietnamese soldiers and headed south to Cam Ranh Bay where he made it off to the smaller vessel.

I was in Vietnam on a presidential pass, so I could have waved my White House orders at the CIA transport guys for a ride to Phnom Penh, and they would have had to do what I wanted. I thought the polite approach was better, however. I found a few pilots in the Air America hanger, and I asked, “Would any of you guys be willing to give me a lift over to Phnom Penh? I know it’s kind of dangerous . . .” They all jumped up, and said in unison, “I’ll take you!” Nothing like a little machismo moment among the CIA’s secret pilot’s society!

PHNOM PENH -- MAR 31: A wounded Cambodian woman is comforted by her husband in a hospital, and later died in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, March 31, 1975. The city was under attack by the Khmer Rouge, who took over the capital less than three weeks later.

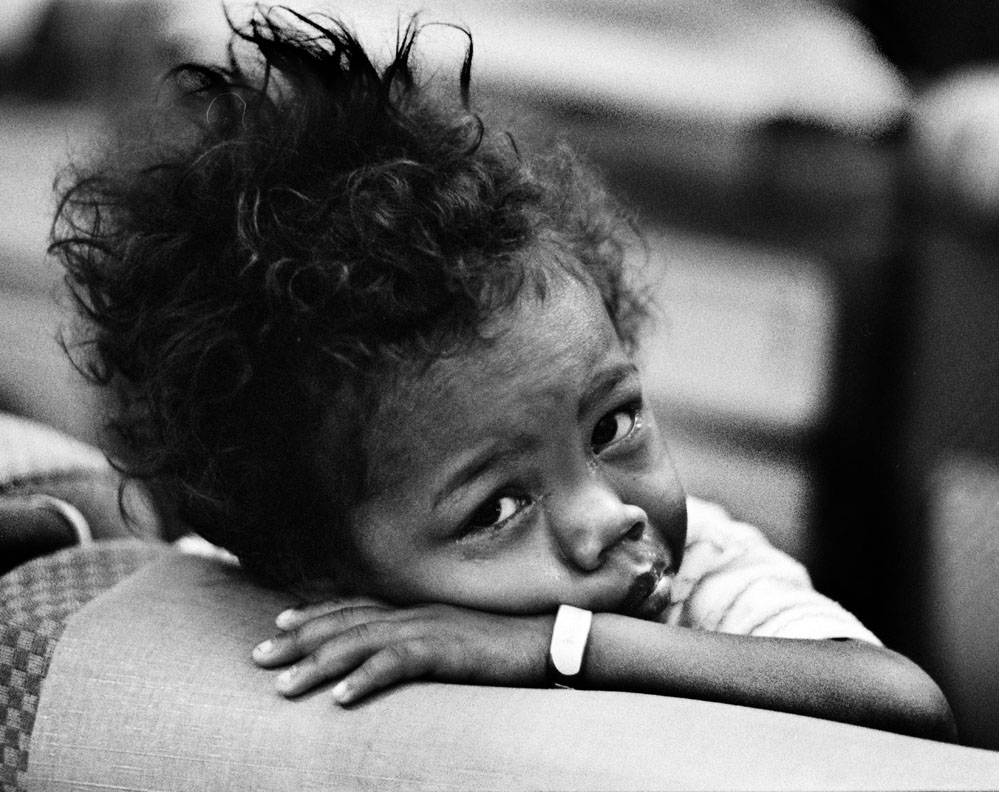

My old friend and colleague, Vietnamese-Lao-Thai-Khmer speaking colleague Matt Franjola was in Phnom Penh working for the Associated Press at the time, so I sent him a message and told him that I was getting a lift over there by a ballsy and intrepid pilot, and asked whether he could pick me up. (I had the good sense not to mention that chauffer was a CIA-employed aviator, flying an Agency-owned aircraft).Pochentong Airport was essentially closed and under constant fire. It was so bad there that the pilot told me as we approached in his Short Take-off and Landing (STOL) airplane that he was going to taxi by the terminal, and that he would slow down, but not stop. In other words, I would have to jump out as he cruised by the sandbagged terminal. And that’s what I did. There was nobody to be seen--except Matt, who was sitting there in his jeep, nonchalant as always, as rockets exploded nearby. We hightailed it out of there, and he took me first for drinks at the old Le Phnom Hotel, our favorite haunt, where I had the special of the day, Martinis and mortars. I also met up with photographer Al Rockoff and some other compatriots from my time working there. Matt caught me up on what was happening, then took me to an overcrowded where I witnessed hundreds of suffereing people wounded in the fighting. I photographed a woman being comforted by here husband. She had been hit by shrapnel, and died while I was there.I made a portrait of a Cambodian refugee girl who was among thousands of people crammed into an unfinished hotel on the banks of the Mekong River. I saw that she wore a dog tog, and its reflection is what caught my eye. Her photo has remained a symbol for me of all the suffering that kids the world over experience because of senseless wars. I have been haunted by her ever face ever since, and even traveled back to Phnom Penh several years ago to try and find her, but with no luck.

Later that afternoon Matt dropped me at the U.S. Embassy where I recieved a Top Secret briefing on the grave situation in Cambodia by Ambassador John Gunther Dean and his staff. I vividly recall being in the tactical operations center looking at a map showing large red arrows representing the advancing Khmer Rouge coming from all directions toward the capital of Phnom Penh. We were surrounded. The embassy staff was already preparing a helicopter exodus for U.S. citizens and some allies if the situation deteriorated further. Dean painted a horrible and compelling picture about what might happen to Americans and their Cambodian counterparts who chose to remain. When Matt collected me after the briefing I told him way off the record that there was going to be an evacuation soon, and urged him not to play hero and stay, but get his ass out. He had never heard me sound so serious, and that got his attention. A few days later the U.S. commenced Operation Eagle Pull, and evacuated all the Americans and high risk Cambodians who wanted to leave Phnom Penh. Matt had considered staying, but with my voice ringing in his ears, decided to take the last helicopter out, and went from the frying pan into the fire, ending up in Saigon where he stayed after it fell to the Communists. After reporting that story, he safely got out of there also.

PHNOM PENH -- MAR 31: A little Cambodian refugee girl with a dog tag as a trinket in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, March 31, 1975. Cambodia was taken over by the Khmer Rouge a few weeks later, and her fate is unknown. This picture won a first prize in the 1976 World Press Photo contest. PHNOM PENH -- MAR 31: A Cambodian refugee child in a hospital, Phnom Penh, Cambodia, March 29, 1975. Cambodia was taken over by the Khmer Rouge a few weeks later, and her fate is unknown.

I returned to Saigon in time to attend a meeting at which General Weyand and his crew met with the beleaguered South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu in his office at Saigon’s Presidential Palace. It wasn’t a pleasant meeting and the Americans didn’t have much to offer him. As I took a photo of Thieu at his desk, a traditional Vietnamese painting behind him, I wondered how much longer he would be in that chair. Only eighteen days more as it turned out.

SAIGON -- APR 3: South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu in his office at the Presidential Palace in Saigon, South Vietnam, April 3, 1975. Thieu was waiting for a meeting with U.S. Army Chief of Staff Gen. Fredrick Weyand and U.S. Ambassador to South Vietnam Graham Martin who were there on orders from U.S. President Gerald R. Ford to see if anything could be done to slow down or halt the advancing North Vietnamese Communists.

Later I that night I reconnected with Ken Quinn. He and his collaborators were real heroes, saving countless lives of high-risk Vietnamese who had worked with the Americans and might well have been executed had Quinn and his team been unable to facilitate their evacuation. Ken and his contacts around the country were incredibly pessimistic about the outcome for Vietnam. His comments and observations, combined with my firsthand look at a country coming unspooled, was going to lead to a tough report for the president.

SAIGON -- APR 3: South Vietnamese President Ngyen Van Thieu in his office at the Presidential Palace in Saigon, South Vietnam, April 3, 1975 meets with U.S. Army Chief of Staff Gen. Fredrick Weyand and U.S. Ambassador to South Vietnam Graham Martin who were there on orders from U.S. President Gerald R. Ford to see if anything could be done to stop a Communist takeover.

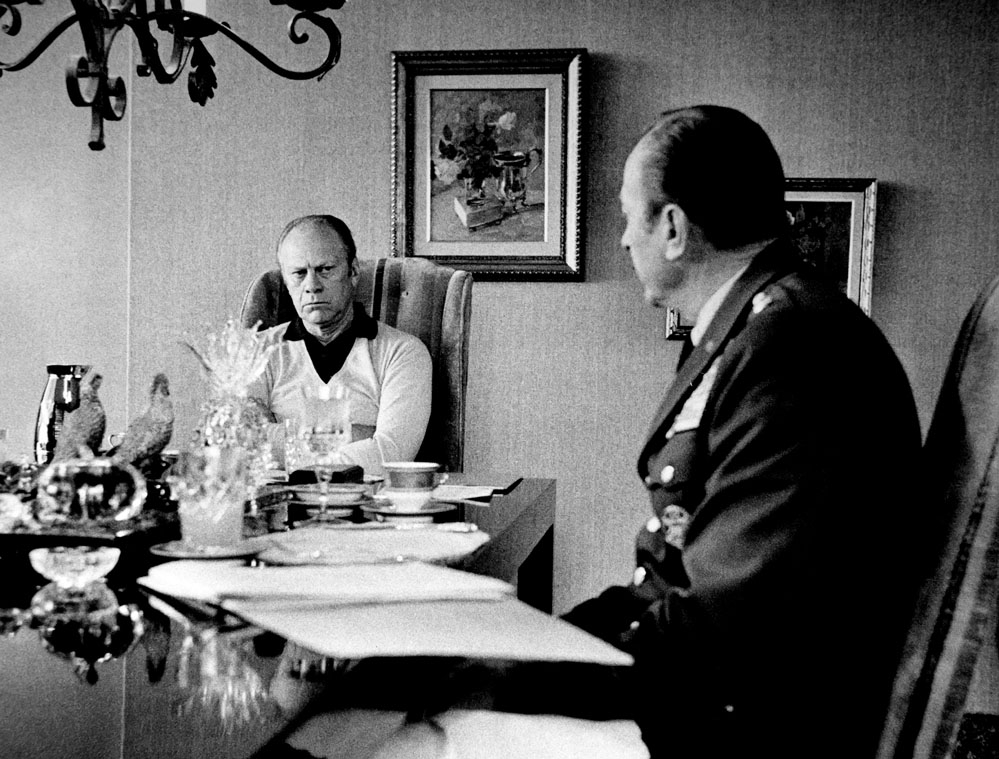

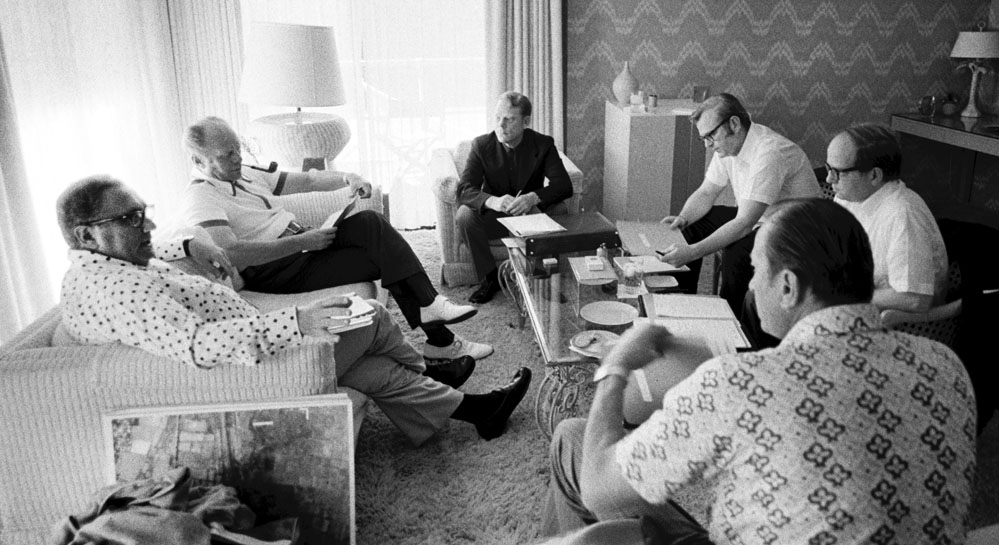

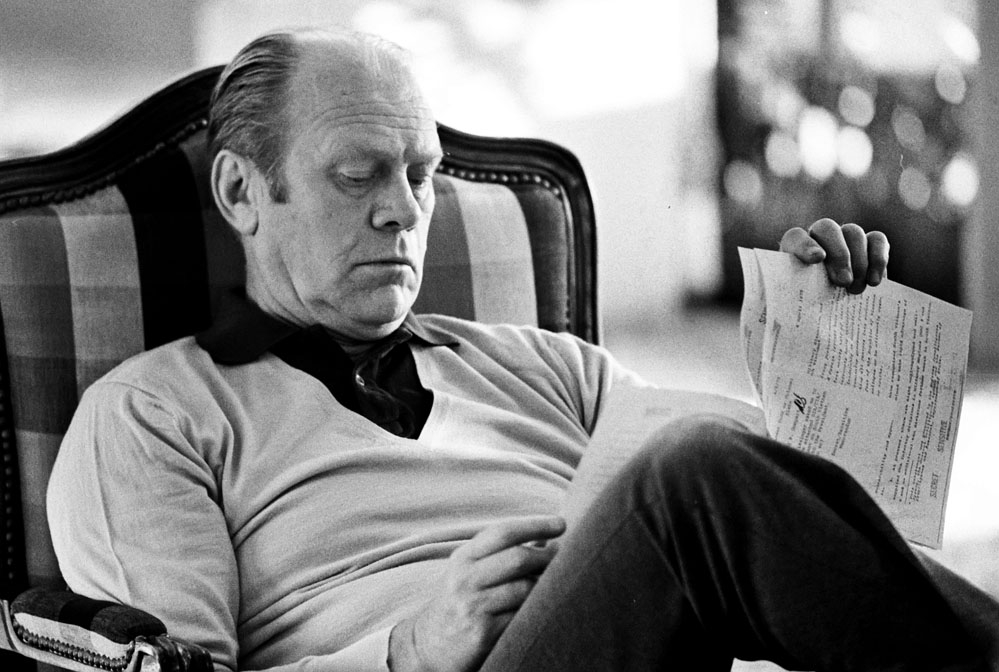

Gen. Weyand made his presentation to President Ford at the president’s home in Palm Springs. Weyand wasn’t optimistic, but held out some hope that the encroaching North Vietnamese might be held off if Congress allotted more money for assistance. The president clearly didn’t like what he was hearing.

PALM SPRINGS -- APR 5: U.S. President Gerald R. Ford meets with Army Chief of Staff Gen. Frederick Weyand after his return from a fact finding mission to South Vietnam that was being attacked by the advancing North Vietnamese army. Weyand briefed the president on his trip in Palm Springs, California, April 5, 1975.

My new friends from the CIA pretty much corroborated the assessment I had given the president. In this rare photo of CIA officials directly briefing the president, Chief of the East Asia Division of the CIA Ted Shackley, (who was known as “the Blond Ghost,” According to Wikipedia, Shackley's work included being station chief in Miami, during the period of the Cuban Missile Crisis, as well as head of the Cuban Project, known as Operation Mongoose, which he directed. He was also said to be the director of the Phoenix Program during the Vietnam War, as well as the CIA station chief in Laos between 1966–1968, and ran the secret war there. He was also CIA Saigon station chief from 1968 through February 1972. In 1976, he was appointed Associate Deputy Director for Operations, and put in charge of the CIA's worldwide covert operations. His nickname should really have been, "Super Spook." ). CIA Deputy Director for National Intelligence Officers George Carver who was in the meeting also weighed in, and the two of them gave the president their straightforward assessment.

PALM SPRINGS -- APR 5: 2:57-4:54 PM. President Gerald R. Ford meets with (L-R) Erich F. von Marbod, Comptroller and logistics expert, Department of Defense, Theodore G. Shackley, Chief, East Asia Division, Central Intelligence Agency, George A. Carver, Jr., Deputy to the Director of Central Intelligence for National Intelligence Officers, CIA, Army Chief of Staff Gen. Frederick Weyand, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. Weyand led a group of CIA and Defense Department officials to Saigon to assess the deteriorating situation there, and reported back to the President in Palm Springs, California, April 5, 1975.

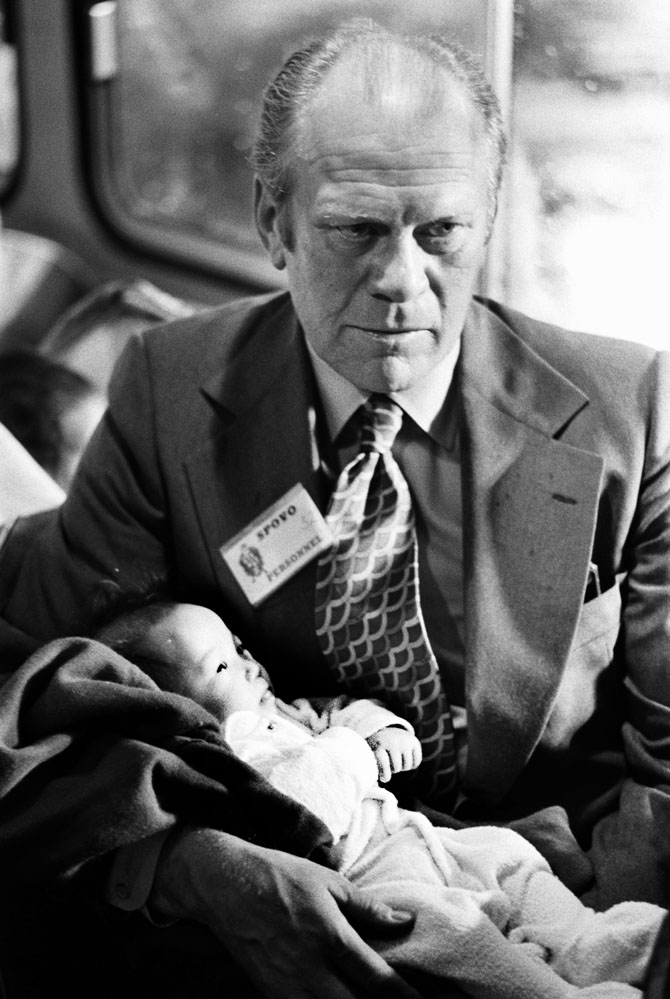

The President and Mrs. Ford flew up to San Francisco after his briefing by Gen. Weyand and his associates to greet a planeload of Vietnamese orphans arriving in the U.S. It was a sobering sight. Many of the kids had American fathers, and were considered to be at risk if the Communists took over. Those "Amerasian" kids who didn’t make it out were treated like second-class citizens or worse.Operation Babylift was the mass evacuation of children ordered by President Ford from South Vietnam to the United States and other countries at the end of the Vietnam War on April 3–26, 1975. By the final flight out of South Vietnam, over 3,300 infants and children had been evacuated. Along with Operation New Life, over 110,000 refugees were evacuated from South Vietnam at the end of the Vietnam War. Thousands of children were airlifted from Vietnam and adopted by families around the world.

SAN FRANCISCO -- APR 5: President Gerald R. Ford carries one of the first children evacuated from Vietnam during Operation Babylift at San Francisco Airport. The president was taking the child from a chartered Pan Am flight, San Francisco, California, April 5, 1975.Operation Babylift was the mass evacuation of children ordered by President Ford from South Vietnam to the United States and other countries at the end of the Vietnam War on April 3–26, 1975. By the final flight out of South Vietnam, over 3,300 infants and children had been evacuated. Along with Operation New Life, over 110,000 refugees were evacuated from South Vietnam at the end of the Vietnam War. Thousands of children were airlifted from Vietnam and adopted by families around the world.

SAN FRANCISCO -- APR 5: President Gerald R. Ford on a bus with one of the first children evacuated from Vietnam during Operation Babylift, San Francisco Airport, April 5, 1975.Operation Babylift was the mass evacuation of children ordered by President Ford from South Vietnam to the United States and other countries at the request of the Vietnamese government and non governmental organizations who ran orphanages and relief agencies toward the end of the Vietnam War. The operation ran from April 3 through 26, 1975. By the final flight out of South Vietnam, over 3,300 infants and children had been evacuated. Along with Operation New Life, over 110,000 refugees were evacuated from South Vietnam at the end of the Vietnam War. Thousands of children were airlifted from Vietnam and adopted by families around the world. There was one tragedy associated with the airlift, an Air Force C-5A with orphans crashed killing 138 people, including 78 children.

The next day, armed with a stack of black and white photographs that I had taken on my Vietnam expedition, I presented President Ford with an extremely unpleasant show and tell. We went through the photos one by one. He saw the evacuation of Nha Trang, the ships full of fleeing South Vietnamese soldiers in Cam Ranh Bay, and the refugee children in Cambodia. I said, “Anyone who says that Vietnam has more than three or four weeks left is bullshitting you.” I told him that what I saw, along with the observations of the people in Vietnam that I respected, and my knowledge of the country, added up to only one conclusion for the future of the conflict -- “the party’s over.” When we got back to the White House a couple of days later I had all the colorful photos of cheery presidential social events replaced with large stark black and white pictures of my documentation of the impending end of Vietnam and Cambodia. During the night an offended White House staffer took them down. The president was furious, and ordered them put back on the West Wing walls. “Leave them up,” he said emphatically, “everyone should know what’s going on over there.” (The power of photography: The president later told me that those photos and my account of the suffering influenced his thinking on allowing more than 125,000 Vietnamese refugees to enter the United States).

PALM SPRINGS -- APR 5: 2:05 PM. President Gerald R. Ford reads Gen. Frederick Weyand's report about the deteriorating situation in Vietnam. Weyand wasn't at all optimistic, but thought there was still a chance to prop up the S. Vietnamese government with more aid. Palm Springs, California, April 5, 1975.

Thousands of children were airlifted from Vietnam and adopted by families around the world. There was one tragedy associated with the airlift, an Air Force C-5A with orphans crashed killing 138 people, including 78 children.

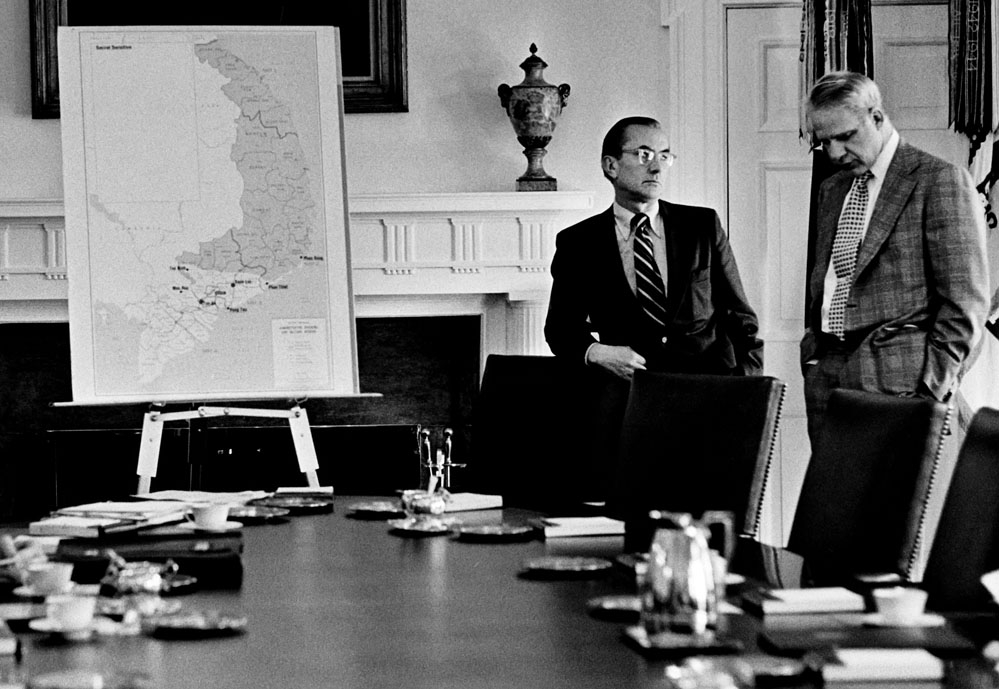

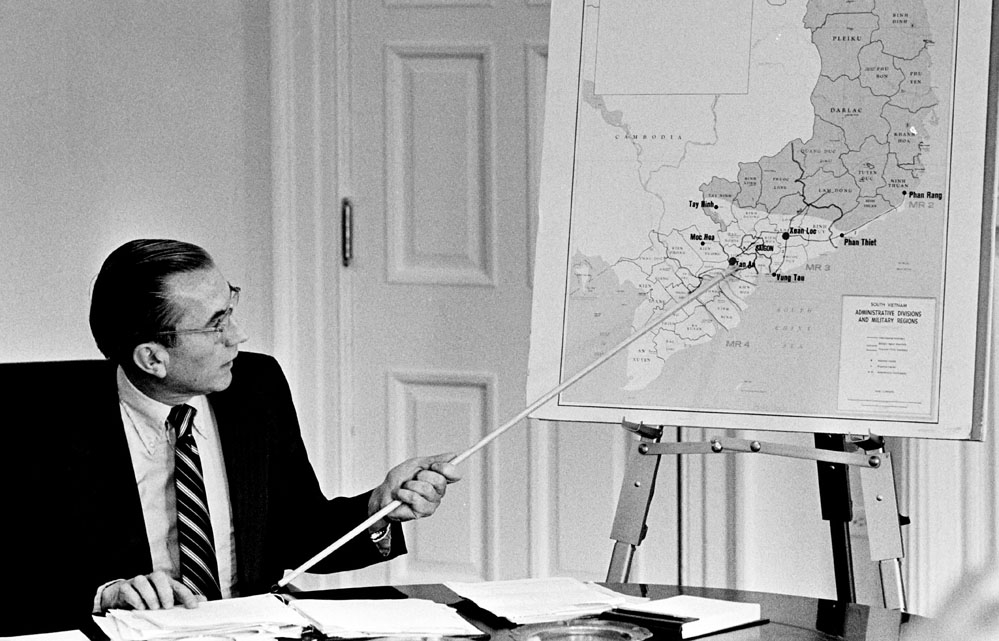

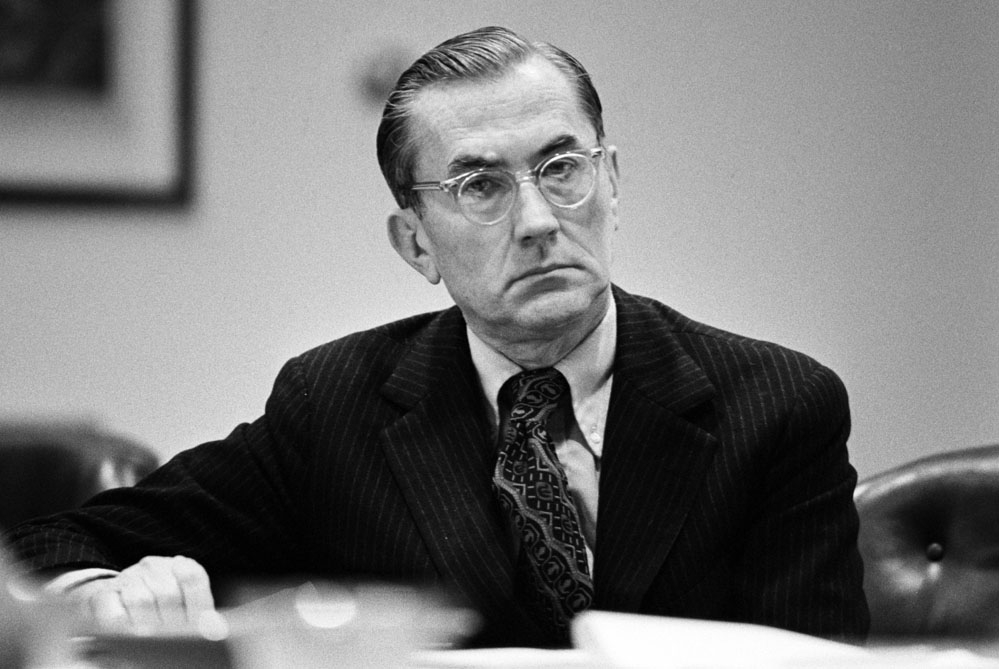

By the time we got back to the White House, the North Vietnamese forces were getting closer to Saigon. Most of the northern part of the country had already fallen, and only a part of the south is left. Both CIA Director Colby and Secretary of Defense Jim Schlesinger appeared a bit morose when I photographed them in the Cabinet Room prior to an NSC meeting on Indochina.

CIA Director Bill Colby is pointing to a map of Vietnam and directing attention to Xuan Loc, a town only fifty miles east of Saigon. He briefs about heavy fighting in the area after attacks from a North Vietnamese Army division using armor and artillery. Colby quotes intelligence that says fighting will intensify and the North Vietnamese are trying to achieve victory this year, not 1976 as earlier predicted. He says Communist victories have “far exceeded their expectations and have created ‘the most opportune moment’ for total victory this year.” They will press the attack in surrounding province, and attack Saigon when the time comes. Colby continued by saying that 18 infantry divisions were already in the south, and more on the way. “On paper, the GVN’s (Government of Vietnam’s) long-term prospects are bleak, no matter how well Saigon’s forces and commanders acquit themselves in the fighting that lies ahead.” (quoted from NSC minutes of the meeting). He went on to say, “Another factor is U.S. aid. A prompt and large-scale infusion would tend to restore confidence.

WASHINGTON -- APR 9: CIA Director William Colby points out Communist advances in Xuan Loc on a map of Vietnam in the Cabinet Room at the White House during a meeting of the NSC regarding the Communist advances in S. Vietnam, Washington, D.C., April 9, 1975. Colby said that long term prospects for the government of South Vietnam "were bleak."

The converse is obviously also true. The most likely outcome is a government willing to accept Communist terms, i.e. surrender.”Colby also reported that Cambodia couldn’t hold on for more than another week. (In fact the American evacuation of Phnom Penh was ordered two days later.)The discussion turned to how many people to evacuate and whether to ask Congress for money to fund an evacuation in the president’s speech the following night in front of a joint session. President Ford said, “If we have a disaster, Congress will evade the responsibility. Let us get some language. I am sick and tired of their asking us to ignore the law or to enforce it, depending on whether or not it is to their advantage.”

President Ford allows some anxiety to show after ordering the execution of Operation Eagle Pull that will evacuate all Americans from Cambodia, On April 21, and more than a week after the Cambodian operation was complete, the president and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger focused on the continuing problems in Vietnam. In a classified conversation, Kissinger said he talked to Soviet Ambassador Dobrynin about arranging a ceasefire to get Americans out. He then discussed problems with American ambassador to South Vietnam Graham Martin going rogue.

Kissinger said, “I worried about Martin being Chinese Gordon* and causing a panic to prove he was right. So we have to treat him with care. I am afraid Martin accelerated Thieu’s departure.” Brent Scowcroft added, ”His (Martin’s) talk with Thieu must have been provocative because of his quick action and blast at you.” Kissinger said, “Martin should be told that our judgment is as soon as the airport comes under fire, the DAO personnel at Tan Son Nhut should be immediately taken out by C-130, not helicopters . . . he should not delay a move at Tan Son Nhut until it is irretrievably closed.”*Charles “Chinese” Gordon was a British army officer and administrator who made his military reputation in China, where he was placed in command of the "Ever Victorious Army," a force of Chinese soldiers led by European officers. In the early 1860s, Gordon and his men were instrumental in putting down the Taiping Rebellion, regularly defeating much larger forces. For these accomplishments, he was given the nickname "Chinese" Gordon and was honored by both the Emperor of China and the British. (From Wikipedia)On April 23, the situation in Vietnam was clear to the president, and he wasn’t afraid to acknowledge the fact. At a speech to students at Tulane University he said, “Today, America can regain the sense of pride that existed before Vietnam. But it cannot be achieved by refighting a war that is finished as far as America is concerned. As I see it, the time has come to look forward to an agenda for the future, to unify, to bind up the Nation's wounds, and to restore its health and its optimistic self-confidence.” This was the first time he publicly said that the war was “finished.”

During an NSC meeting, and as the Vietnam situation was heading off the edge of the cliff, the president was told by Secretary of Defense James Schlesinger that there were approximately 1700 Americans left in Saigon. The president said he wanted that number down to 1090 by Friday night. Schlesinger said, “That is a lot in one day.” The president replied, “That is what I ordered. There will be another order that by Sunday all non-essential anon-governmental personnel must be out of there. The group that is left will stay until the order is issued to take them all out.” The president’s main concern was that the rate of evacuation not induce panic among the Vietnamese.

WASHINGTON -- APR 24: 4:45 to 5:15 PM. President Gerald R. Ford meets with the National Security Council in the Cabinet Room at the White House and is briefed on how the evacuation of Americans from Saigon was going. (L-R) Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, Vice President Nelson Rockefeller, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. George Brown. CIA Director William Colby, Deputy Secretary of State Robert Ingersoll, President Ford, Secretary of Defense James Schlesinger, April 24, 1975.

This emergency meeting of the National Security Council was convened after the president got news that two U.S. Marines were killed by enemy fire at Ton San Nhut Airport and that North Vietnamese were within artillery range of the airport. Clearly, the US had very little time left to act and Ford had decided to bring the war to a conclusion. Seated around the table were America’s heavy hitters -- the president, vice president, secretary and deputy secretary of state, secretary and deputy secretary of defense, chairman of the joint chiefs of staff, director of the CIA, and the White House chief of staff. This discussion of the final phase of the evacuation of Vietnam was not only a dramatic situation of great historical importance, but was also deeply personal for me. I was in the room and watching a war that I covered for over two years end in real time and before my eyes. Granted, we all knew it was coming, but this meeting was the last formal gathering of the men who would execute the president’s orders to pull the plug on a ten-year long debacle.

WASHINGTON DC - APRIL 28: 7:23-8:08 PM: At a meeting of the National Security Council in the Roosevelt Room, Ford makes the decision to continue to evacuate Americans and high risk Vietnamese from Vietnam from Saigon's Tan Son Nhut Airport, April 28, 1975 in Washington DC. Also in the meeting, (from left), CIA Director William Colby, Deputy Secretary of State Robert Ingersoll, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, Secretary of Defense James Schlesinger, Deputy Secretary of Defense Bill Clements, Vice President Nelson Rockefeller, and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General George Brown.

Chairman of the Joint Chiefs Gen. George Brown talked about bringing in 70 sorties of C-130s into Tan Son Nhut, with 35 aircraft coming in twice to evacuate the remaining 400 members of the Defense Attaché Office based there. He said the controller on the ground would have the discretion about whether this operation was feasible. Brown’s concern was, “the report of an aircraft being shot down by an SA-7 [a shoulder-fired surface to air missile]. Choppers or aircraft are defenseless against the SA-7” He continued, “Of course we have to do our mission, but if the risk becomes too great, we may need to turn off the lift.”

WASHINGTON DC - APRIL 28: 7:23-8:08 PM: Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General George S. Brown at a meeting of the National Security Council in the Roosevelt Room as President Gerald R. Ford makes the decision to continue to evacuate Americans and high risk Vietnamese from Vietnam from Saigon's Tan Son Nhut Airport, April 28, 1975 in Washington DC. Also in the meeting, (from left), CIA Director William Colby, Deputy Secretary of State Robert Ingersoll, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, Secretary of Defense James Schlesinger, Deputy Secretary of Defense Bill Clements, Vice President Nelson Rockefeller.

(Direct quotes are from official minutes of the meeting, now declassified): CIA Director William Colby opened the discussion at this NSA meeting with a report that, “the Viet Cong have rejected [now S. Vietnamese President] Minh’s cease-fire offer. They have added a third demand, which is to dismantle the South Vietnamese armed forces.” He went on to say that the situation had become more dangerous, and that enemy artillery was, “within range of Tan Son Nhut airport. At 4:00 a.m. they had a salvo of rockets against Tan Son Nhut. This is what killed the Marines.” He also said that surface to air missiles had been deployed in the area further increasing the risk factor.

WASHINGTON DC - APRIL 28: 7:23-8:08 PM: As a key member of the National Security Council, CIA Director William Colby is part of the discussion at a meeting of the NSC in the Roosevelt Room, President Gerald R. Ford makes the decision to continue to evacuate Americans and high risk Vietnamese from Vietnam from Saigon's Tan Son Nhut Airport, April 28, 1975 in Washington DC.

At the end of the meeting on April 24th the president said, “I understand the risk. It is mine and I am doing it. But let’s make sure we carry out the orders. Vice President Rockefeller said, “You can’t insure the interests of America without risks.” The president said, “With God’s help.” Vice President Rockefeller said, “It take real courage to do what is right in these conditions.”The NSC meeting ended.

WASHINGTON -- APR 24: 4:45 to 5:15 PM. President Gerald R. Ford reacts during meeting with the National Security Council in the Cabinet Room of the White House after he was briefed on how the evacuation of Americans out of Saigon was going. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, Vice President Nelson Rockefeller, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. George Brown, CIA Director William Colby, Deputy Secretary of State Robert Ingersoll, and Secretary of Defense James Schlesinger were in the meeting, April 24, 1975.

News came that no one wanted to hear. Henry Kissinger reported that the runways at Tan Son Nhut could not be used for evacuation. Worse, the population had gotten out of control and had flooded the runways. It was now impossible to land any more fixed wing aircraft. It was time to consider implementing Option 3, codenamed, “Operation Frequent Wind,” the final evacuation of Saigon by helicopter was at hand

The discussion then turned to what would happen if the U.S. fired on the advancing North Vietnamese to protect the evacuation. Secretary Kissinger said, “I think that, if we fire, we have to pull out the entire Embassy . . . The North Vietnamese have the intention of humiliating us and it seem unwise to leave people there.” The President said, “I agree. All should leave. We have now made two decisions: First, today is the last day of Vietnamese evacuation. Second, if we fire, our people will go. Are we ready to go to a helicopter lift?Gen. Brown replied, “Yes, if you or Ambassador Martin say so, we can have them there within an hour.”Kissinger said, “We should not let it out that this is the last day of civilian evacuation.”There was more discussion about how this would work, and if Tan Son Nhut was closed, starting the helicopter evacuation. General Brown said, “I do not want to see Americans standing there waiting for the last plane.” He also recommended that air cover come in to secure a helicopter lift.The president concluded the meeting by saying, “We can wait until we see whether the C-130s can get in. If they cannot we go to Option 3, (final evacuation by helicopters). The decision will be forced by whether the C-130s can or cannot operate. Is that agreed?” All Nod.

WASHINGTON DC - APRIL 28: 7:23-8:08 PM: Secretary of State Henry Kissinger at a meeting of the National Security Council in the Roosevelt Room as President Gerald R. Ford makes the decision to continue to evacuate Americans and high risk Vietnamese from Vietnam from Saigon's Tan Son Nhut Airport, April 28, 1975 in Washington DC.

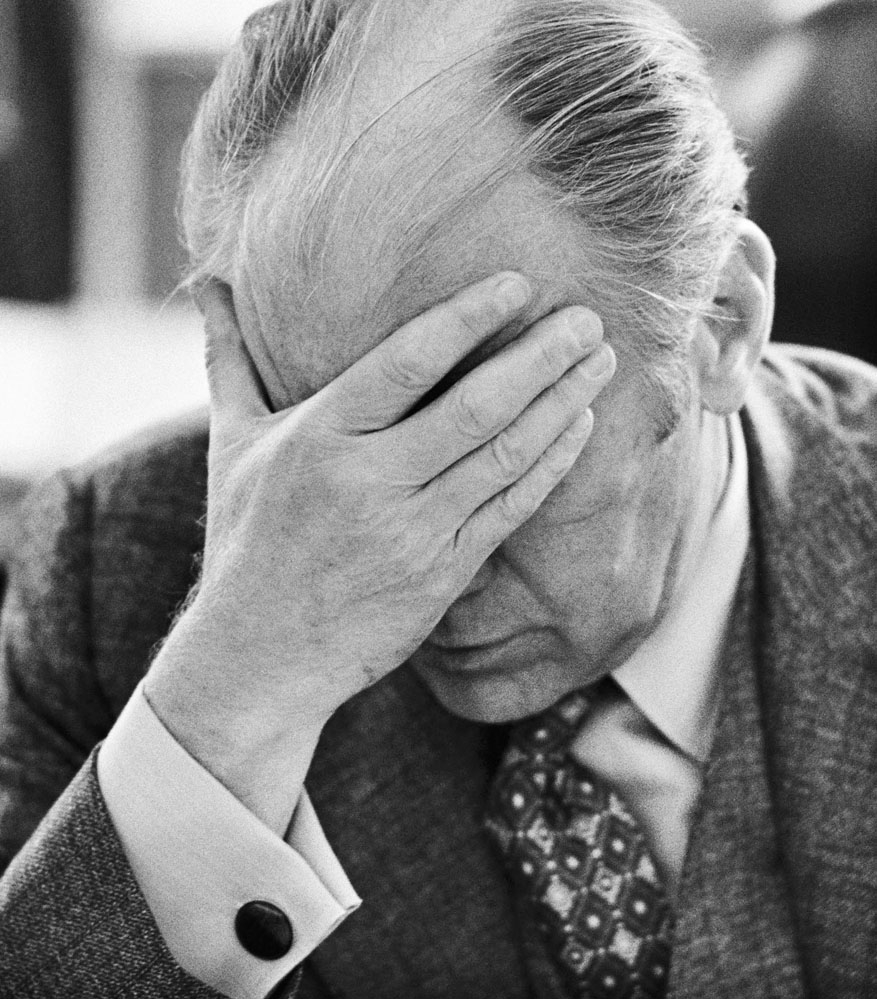

America has lost the war in Vietnam. The weight of that reality is evident as President Ford talks to Secretary of Defense Schlesinger and orders the implementation of “Operation Frequent Wind,” the final evacuation of Americans from Vietnam. Mrs. Ford and I were the only other people in the room with the president when he made the final call, and although he had no choice, it was a tough one for him.

White House Chief of Staff Don Rumsfeld keeps track of the fast moving situation. A few months later he would become President Ford’s Secretary of Defense, the nation’s youngest ever, and then almost 25 years later President George W. Bush’s Defense Secretary, and with it the Guinness World Record of being the nation’s oldest SECDEF.

The President of the United States is the person who has the final word on the big decisions. I always found humanity to be the foundation of every judgment that President Ford made. On this night he made one of the toughest decisions of his life. Here he contemplates the ramifications with his wife First Lady Betty Ford at his side. It was sad to see this honorable person have to make such a difficult, but necessary call.

By the time this cabinet meeting was convened the evacuation was well underway and only 200 Americans were awaiting a ride out of the U.S. Embassy is Saigon. The president appeared pretty down as the impact of the last few days sunk in.

WASHINGTON -- APR 29: 9:47 AM. President Gerald R. Ford meets with Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, Secretary of Defense James Schlesinger and the rest of his cabinet in the Cabinet Room at the White House to brief them on the progress of the final evacuation of Saigon that was rapidly drawing to a close. Washington, D.C. April 29, 1975.

Of all the Administration officials since those who served Lyndon Johnson’s presidency, Henry Kissinger is one of the most controversial and the most closely identified with the Vietnam War. He was a proponent of Nixon’s “Vietnamization” of the conflict and also played a key role in the bombing of Cambodia to disrupt attacks on South Vietnam by the Communists. Kissinger, along with North Vietnam’s Le Duc Tho, won the 1973 Nobel Peace Prize for helping to establish a ceasefire and the U.S. withdrawal from Vietnam. Tho refused to accept the award, perhaps knowing that they had no intention of honoring the commitment. Not surprisingly the agreement didn’t hold up. The expression on Kissinger’s face reflects this bitter conclusion for a failed U.S. policy and war in the late hours of the final evacuation of Americans from Vietnam.

Secretary of State Kissinger, who is also the National Security Advisor to the president, can only wait for news of the evacuation now happening halfway around the world.

Prior to the meeting of Bi-partisan leaders in the Cabinet Room, the president sat down with Sen. Robert Byrd of West Virginia. This meeting with Byrd and the other Congressional leaders was to answer their questions about the evacuation, and some funding issues that the president was requesting for refugee assistance. The president told them that more than 45,000 high risk Vietnamese had been taken out over the last few days. Secretary Kissinger told them he estimated that 90% of that group would come to the states, but that other countries had been approached to take some as well. He thought that 50,000 would be the top number coming to the states. One of the congressmen said that 50 thousand was all this country could absorb. Secretary Kissinger said, “There is no way the total number can go much beyond 50,000.” He was a bit off in that estimate. By 1980 the number of Vietnamese who escaped Communist rule in their country to U.S. shores was over 230,000, and today’s population of Vietnamese is more than 1,250,000, the sixth largest foreign-born population in the United States.

WASHINGTON -- APR 29: 11:38 AM. President Gerald R. Ford and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger meet with Senator Robert Byrd, (D-WV), in the Cabinet Room at the White House just before Congressional leaders were briefed on the progress of the final evacuation of Saigon that was rapidly drawing to a close. Washington, D.C. April 29, 1975.

Kissinger burst into the president’s economic meeting to tell him that the evacuation of Saigon was almost complete, and he thought Ambassador Martin would be out shortly. I was always amazed that with all the excitement and tension swirling around this operation, it was still business as usual in the White House. The president’s schedule for that day had many meetings related to the Vietnam situation, but many that were not, such as this one.

WASHINGTON -- APR 29: 4:23 PM. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger interrupts a meeting with President Gerald R. Ford and his economic advisors in the oval office at the White House to update the president on the progress of the final evacuation of Saigon that is rapidly drawing to a close. (L-R) (back to camera) Administrator of the Federal Energy Administration Frank Zarb, the president, Deputy Chief of Staff Dick Cheney, Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisors Alan Greenspan, Vice President Nelson Rockefeller, Chief of Staff Donald Rumsfeld, Kissinger, April 29, 1975.

I spent the rest of the evening tracking the main participants who were overseeing the nuts and bolts of the final evacuation. Gen. Scowcroft was at the control center, and all information flowed through him to Secretary Kissinger and other White House officials right up to the president. What I noticed more than anything was the helplessness after the decision was made—there was nothing more they could do, it was up to the military people in the field now.

An air of celebration filled the air when Henry Kissinger gave President Ford the good news that the evacuation was wrapped up. The U.S. Ambassador had finally left, and it was time to move on to the next crisis. I have photographed a few thousand handshakes in my time and find that they tend to pretty much all look alike. This one was no different visually -- the President of the United State congratulating his National Security Advisor/Secretary of State for overseeing the successful evacuation of Americans and thousands of Vietnamese from Vietnam. Unfortunately, this particular "well done" was a bit premature.

WASHINGTON -- APR 29: 5:18 PM. (L-R) Ambassador Robert Anderson, Secret Service Agent, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, unidentified staff, Press Secretary Ron Nessen, and Deputy NSC Advisor Brent Scowcroft head to the Old Executive Office Building where Kissinger will give a press conference announcing the successful conclusion of the helicopter evacuation of the last Americans from Saigon. Unfortunately he was a bit hasty in his proclamation, because after his press conference it was discovered that 11Marines were left stranded on the roof of the U.S. Embassy. They were ultimately rescued less than three hours later, but the war ended as untidily as it started. Washington, D.C., April 29, 1975.

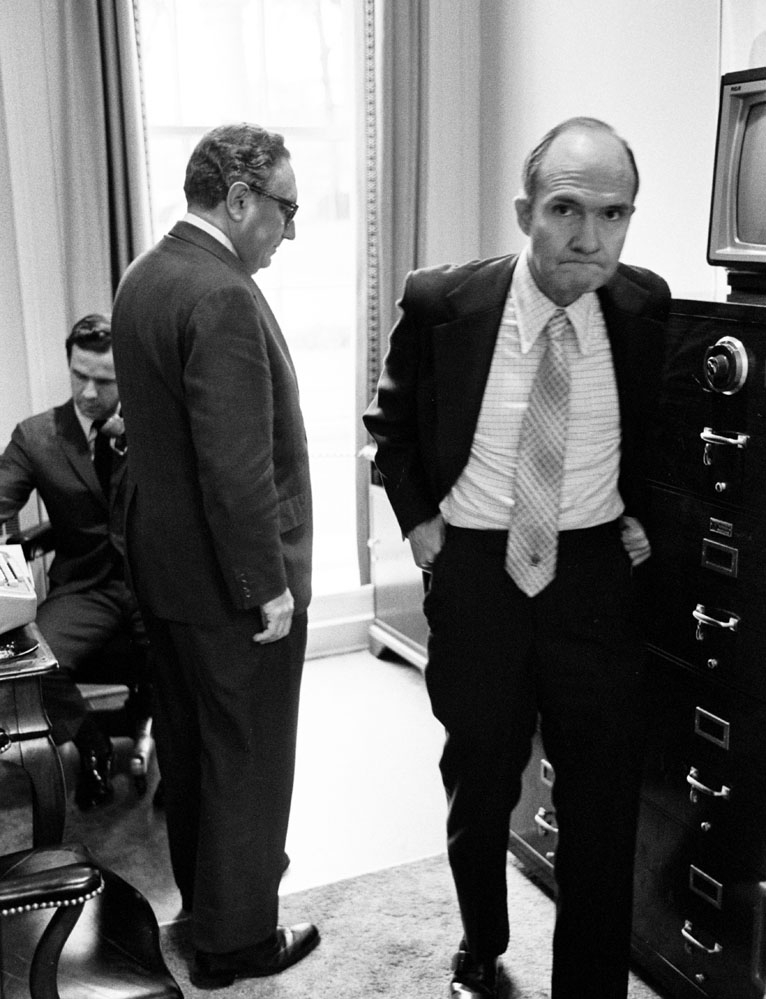

Less than an hour after Kissinger made the decisive statement, “I am confidant that every American who wanted to come out is out . . . “ to the press and the rest of the world, Deputy NSC Advisor Brent Scowcroft drops the bombshell to his boss that 11 Marines were left on the U.S. Embassy roof in Saigon. According to Donald Rumsfeld’s book, “Known and Unknown, “Kissinger and Schlesinger each considered the other’s department responsible for the miscommunication. The president felt Schlesinger bore responsibility and said he was ‘damn mad’ about it”. Rumsfeld thought that what had been told to the American people in the press conference “simply was not true.” He said, “This war has been marked by so many lies and evasions that it is not right to have the war end with one last lie.” The president agreed. Later that year President Ford replaced Schlesinger with Rumsfeld as Secretary of Defense.

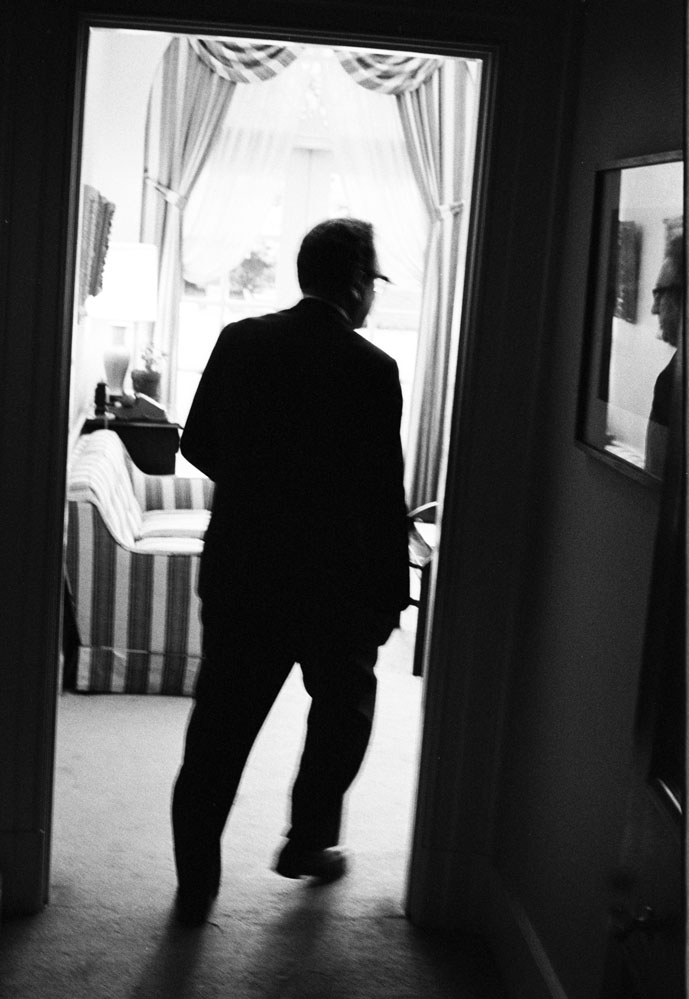

I shadowed Secretary Kissinger during most of the two-day Vietnam evacuation drama. He is where the action was, and was in non-stop motion. I ping ponged back and forth from his NSC quarters, to the oval office, the cabinet room, and wherever the story took me. Not surprisingly, the story was usually Kissinger. A few hours earlier Ambassador Martin had been pleading for more choppers to evacuate more Vietnamese, but time and the president’s patience was running out. He issued a direct order to Martin to get the last Americans out of there, and him with them. Kissinger made a humorous and admiring reference to Martin that, “he got five hundred of his last 100 Vietnamese evacuees out.” At 4:58 pm Washington, DC time Ambassador climbed aboard a helicopter and flew out to the U.S. fleet. For him, and the United States, the Vietnam War was over. Kissinger acknowledged that Martin “ was in a very difficult position. He felt a moral obligation to the people with whom he had been associated, and he attempted to save as many of those as possible. That is not the worst fault a man can have.”As the evacuation was drawing to a close (or so we all thought), I caught the energetic NSC chairman/Secretary of State rounding the corner as he headed into the oval office with an update for the president.

NSC staffers in Kissinger’s office scramble to get information on what was going on, and when – and if – the eleven stranded Marines would be rescued.

Tension grows as Kissinger, Scowcroft, and Kissinger’s military assistant Bud McFarlane wait for news of the stranded Marines. McFarlane, a Marine himself, and a two-tour Vietnam combat veteran, became President Reagan’s national security advisor in 1983, and resigned two years after that when he got caught up in the Iran-Contra affair.

WASHINGTON -- APR 29: 6:13 PM. Deputy National Security Advisor Brent Scowcroft, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, and NSC staffer Robert "Bud" McFarlane in Kissinger's office await word of the fate of 11 Marines who were stranded on the roof of the U.S. Embassy. Fortunately they were rescued a couple of hours later. Washington, D.C., April 29, 1975.

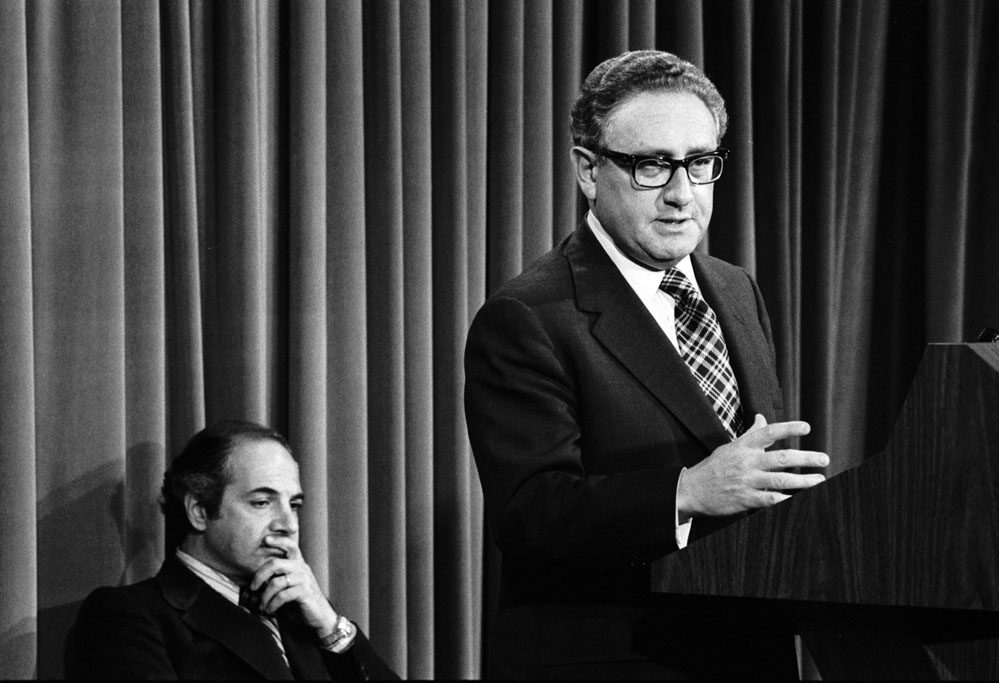

Sec. Kissinger and his entourage walked to the Old Executive Office Building to announce to the press that our latest national nightmare was over after the successful and safe evacuation of all the Americans who wanted to leave Saigon.

WASHINGTON -- APR 29: 5:25 PM. U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger with White House Press Secretary behind him, announces the successful conclusion of the helicopter evacuation of the last Americans from Vietnam in the conference room at the Old Executive Office Building on the White House complex. The announcement was premature after it was learned later that 11 Marines were left stranded on the U.S. Embassy roof in Saigon. They were successfully rescued a few hours after, however, April 29, 1975, Washington, D.C.

Secretary Kissinger and Scowcroft synch their watches as they await word of the eleven Marines being rescued from the U.S. Embassy in Saigon. The choppers were on their way back to Saigon to get them.

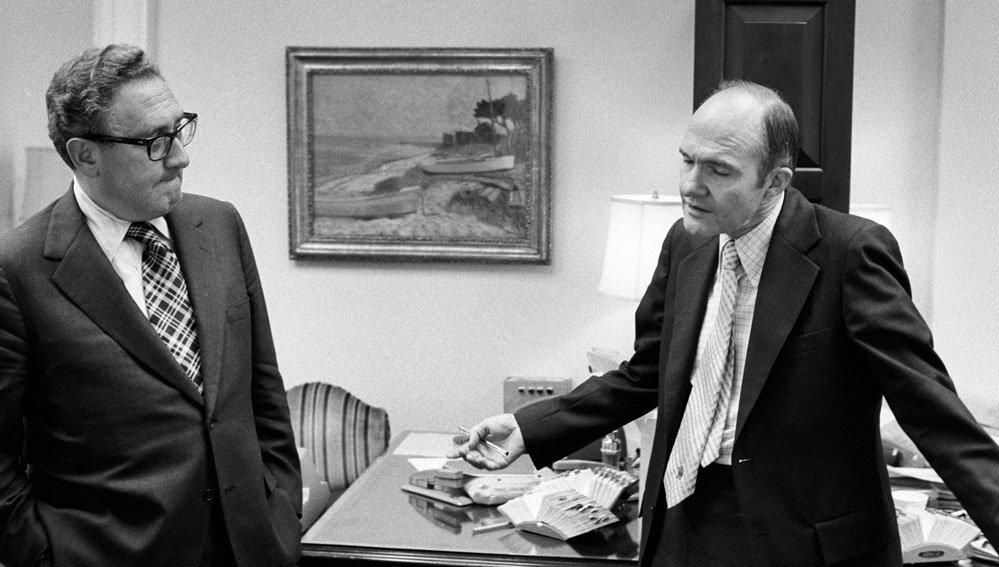

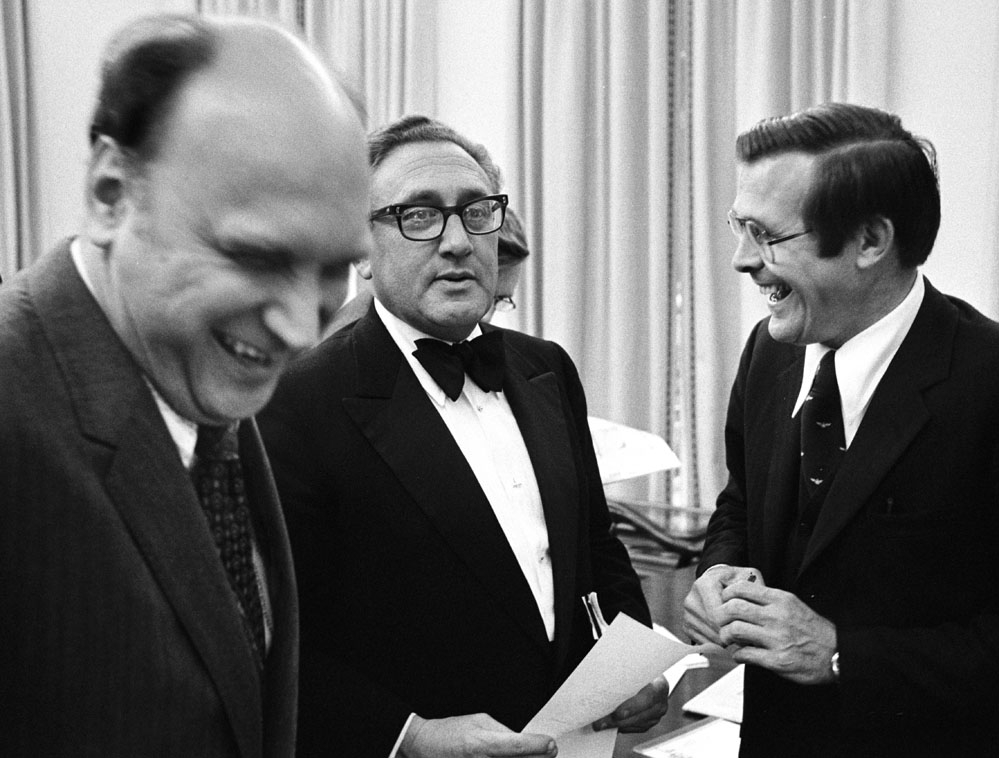

Secretary Kissinger, dressed in formal attire prior to attending the dinner for King Hussein of Jordan, and his deputy Gen. Scowcroft anticipate new of the rescue of the eleven stranded Marines from the embassy in Saigon.

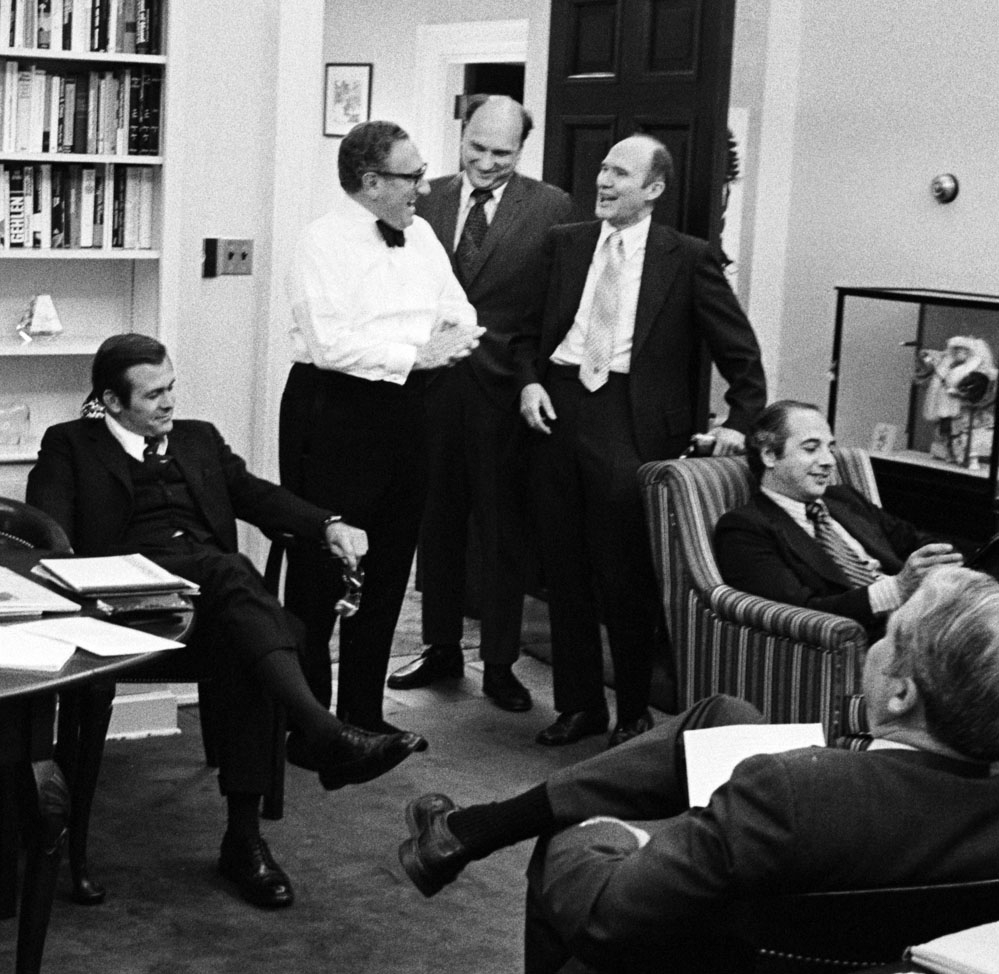

Finally, cause to celebrate. Sec. Kissinger reacts to the news that the 11 Marines have lifted off from the U.S. Embassy safe and sound

WASHINGTON -- APR 29: 8:00 PM. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger in his White House Office reacts to the news that the last Marines in Saigon had been evacuated, by helicopter, signifying the end of the Vietnam War. At left White House chief of staff Donald Rumsfeld, Richard Smyser, NSC staffer, and Deputy NSC advisor Brent Scowcroft, seated White House Press Secretary Ron Nessen, and White House Counselor Jack Marsh in foreground, Washington, DC, April 29, 1975.

It’s over. The Marines were safely rescued, now time to go to dinner with King Hussein. Press Secretary Nessen released this statement after the Marines had been successfully rescued: “Earlier today we announced that the evacuation had been completed. At that time we were not aware that an element of the ground security force remained to be evacuated. Therefore, the completion of the evacuation of these personnel actually occurred after the conclusion of the press conference. Latest reports indicate that the remaining security forces now have been evacuated.”And that was that.

WASHINGTON -- APR 29: 8:01 PM. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger in his White House Office reacts to the news that the last Marines in Saigon had been evacuated by helicopter, signifying the end of the Vietnam War. At right White House chief of staff Donald Rumsfeld, at left Richard Smyser, senior NSC staffer, Washington, D.C., April 29, 1975.

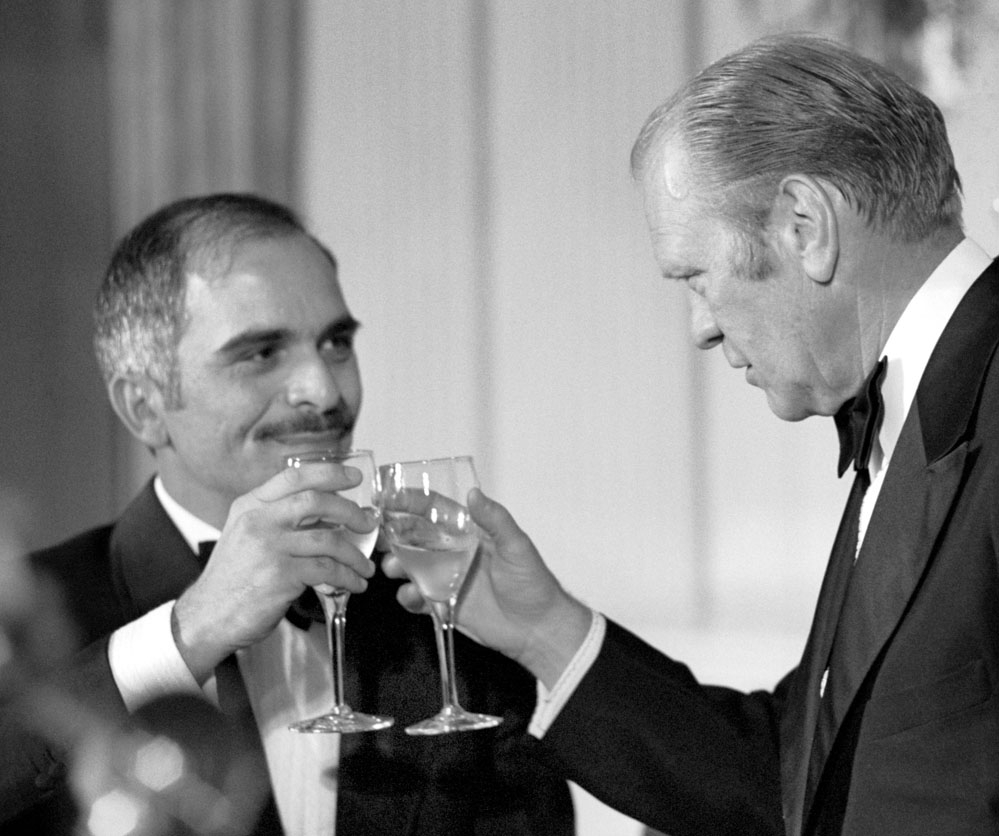

A few minutes after receiving word that the last Marines were finally rescued from the U.S. Embassy, and that the evacuation was this time really over, President Ford stepped back into the dinner with King Hussein. His relief was evident. It was now time for the toast. The president raised his glass and spoke to the close and important relationship with the Kingdom of Jordan. They clinked, had a sip, and everyone applauded. The name “Vietnam” was never mentioned.

After a really long couple of days, I headed to my favorite bar to clink glasses of my own with friends who had also covered the war in Vietnam. And to shed a few tears.

WASHINGTON -- APR 29: 8:11 PM. President Gerald R. Ford toasts His Majesty King Hussein of Jordan at an official dinner for the king in the State Dining Room at the White House. The president had learned minutes earlier that the evacuation of Vietnam was complete, and that all Americans who wanted to leave were safely out, including the U.S. Marines who had been left behind on the embassy roof, April 29, 1975.

Kissinger paces around his office awaiting some word from Saigon about the fate of the trapped Marines. There was major anxiety in the room.

WASHINGTON -- APR 29: 6:15 PM. Deputy National Security Advisor Brent Scowcroft and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger discuss why eleven Marines were stranded on the roof of the U.S. Embassy. They were rescued a couple of hours later. Washington, D.C., April 29, 1975.

President Gerald R Ford stepped out of his dinner with King Hussein of Jordan to take a call in the White House ushers office from Sec. of Defense Jim Schlesinger who told him that at last the eleven Marines who had been left behind on the U.S. Embassy roof in Saigon had finally been rescued, and that the American in involvement in Vietnam was now truly finished. The president is profoundly relieved to learn that all the Marines were safe with no casualties in the final evacuation.

WASHINGTON -- APR 29: 8:01 PM. President Gerald R. Ford takes a call from Defense Secretary James Schlesinger in the White House usher's office informing him that the evacuation of U.S. Marines from the American Embassy in Saigon has been completed, and that the evacuation of Vietnam is finally over. The president was took the call in the middle of a state dinner for His Majesty King Hussein of Jordan, April 29, 1975.