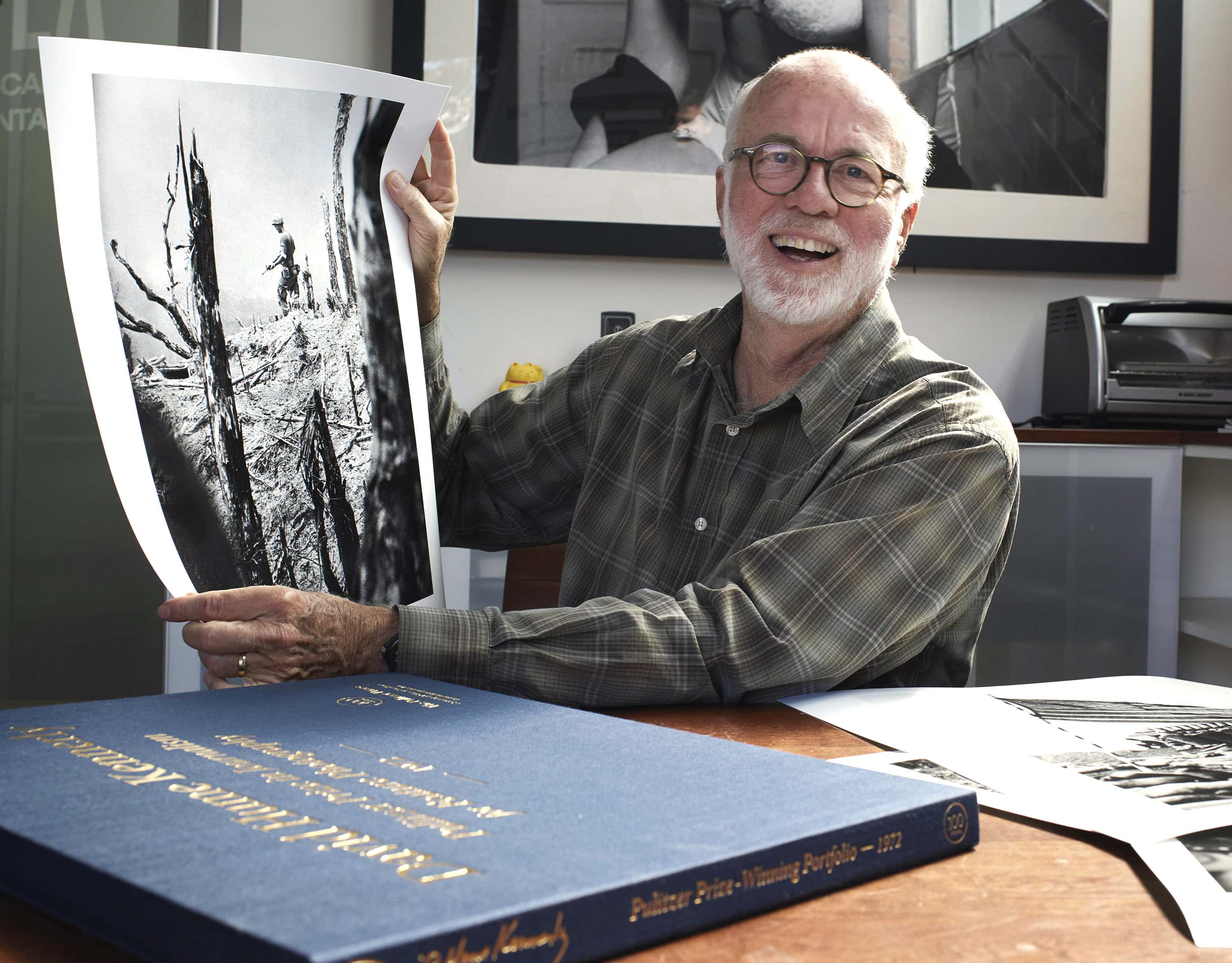

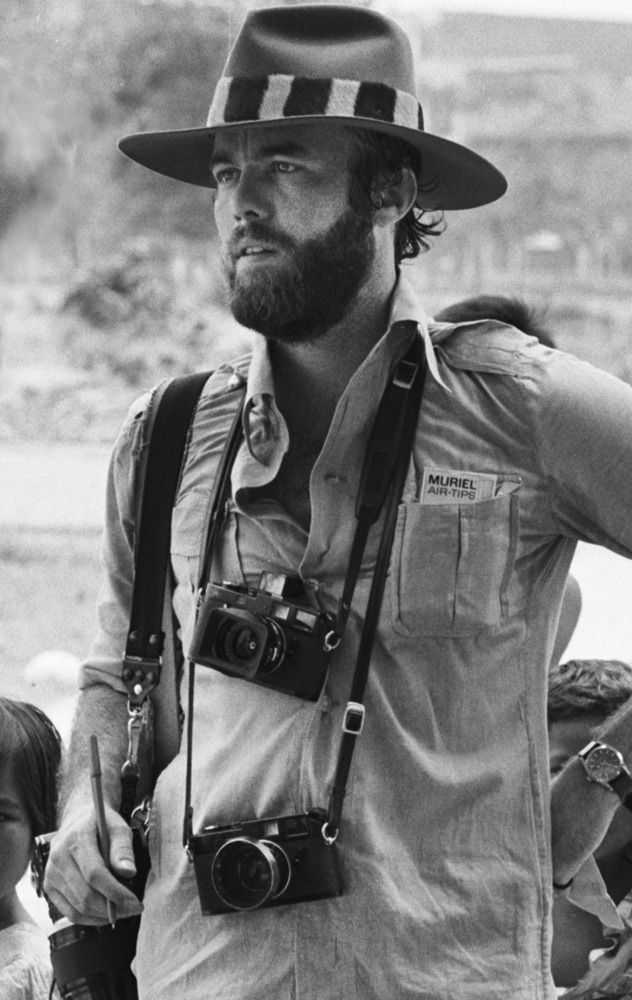

David Hume Kennerly remarks at the

Gen Frederick C. Weyand U.S. Army Pacific HQ Building dedication

Ft. Shafter, Hawaii, August 11, 2023

I would be remiss if I didn’t note that General Charles Flynn, and General Fred Weyand had a couple of things in common. They both commanded the 25th Infantry Division 50 years apart and the U.S. Army Pacific that Flynn now heads, also 50 years apart!

I am grateful that Nancy Hart Kuboyama asked me to give this talk today about her dad, and my friend, the great American General Frederick C. Weyand. Also thanks to Frederick Hart for your terrific remarks about your grandfather.

In the case of my own family, General Weyand and my youngest son James also have something in common. They both graduated from University of California, Berkeley, but Fred beat him to it by over 80 years! In 1976 General Weyand was named Cal’s “Man of the Year,” an honor that no doubt delighted him.

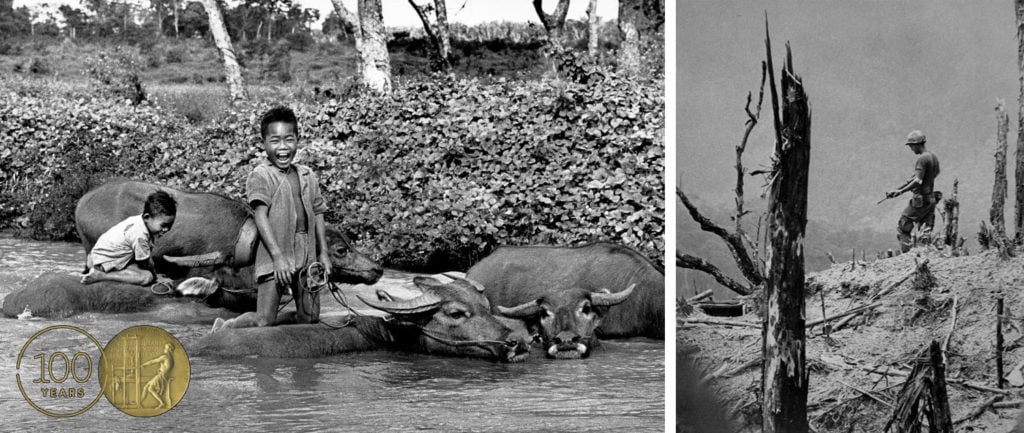

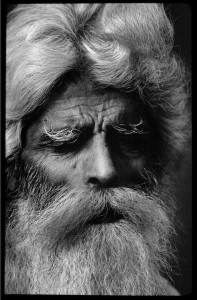

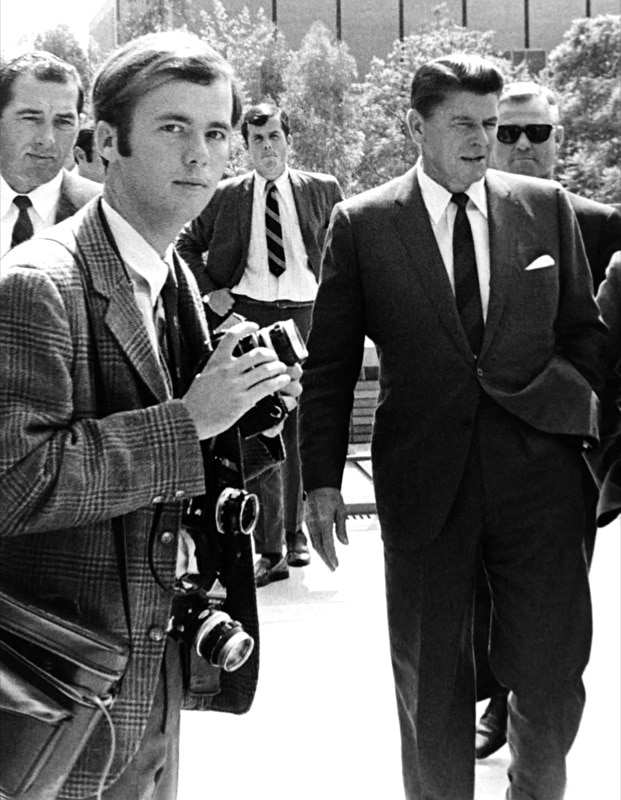

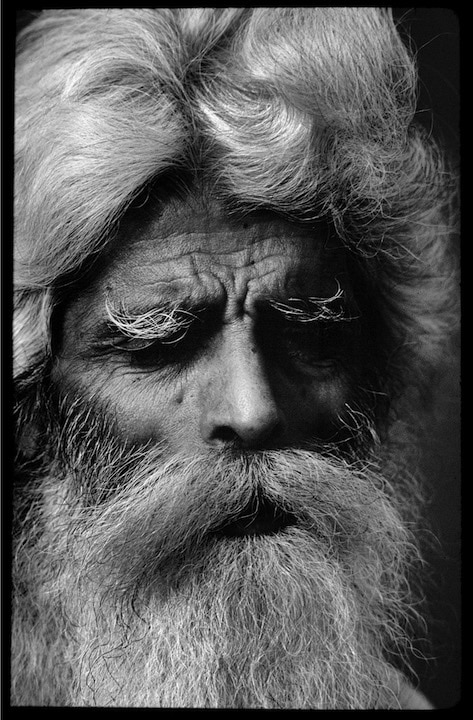

There are so many words to describe Fred Weyand, so I’ll narrow them down to: Brave. Kind. Humble. Compassionate. I recognized that after first meeting him in Saigon in 1972 when he was the last commander of U.S. military operations in Vietnam. He also possessed remarkable diplomatic skills, a vital asset as he guided and led the withdrawal of the last American troops from Vietnam in 1973 that ended direct U.S. combat operations.

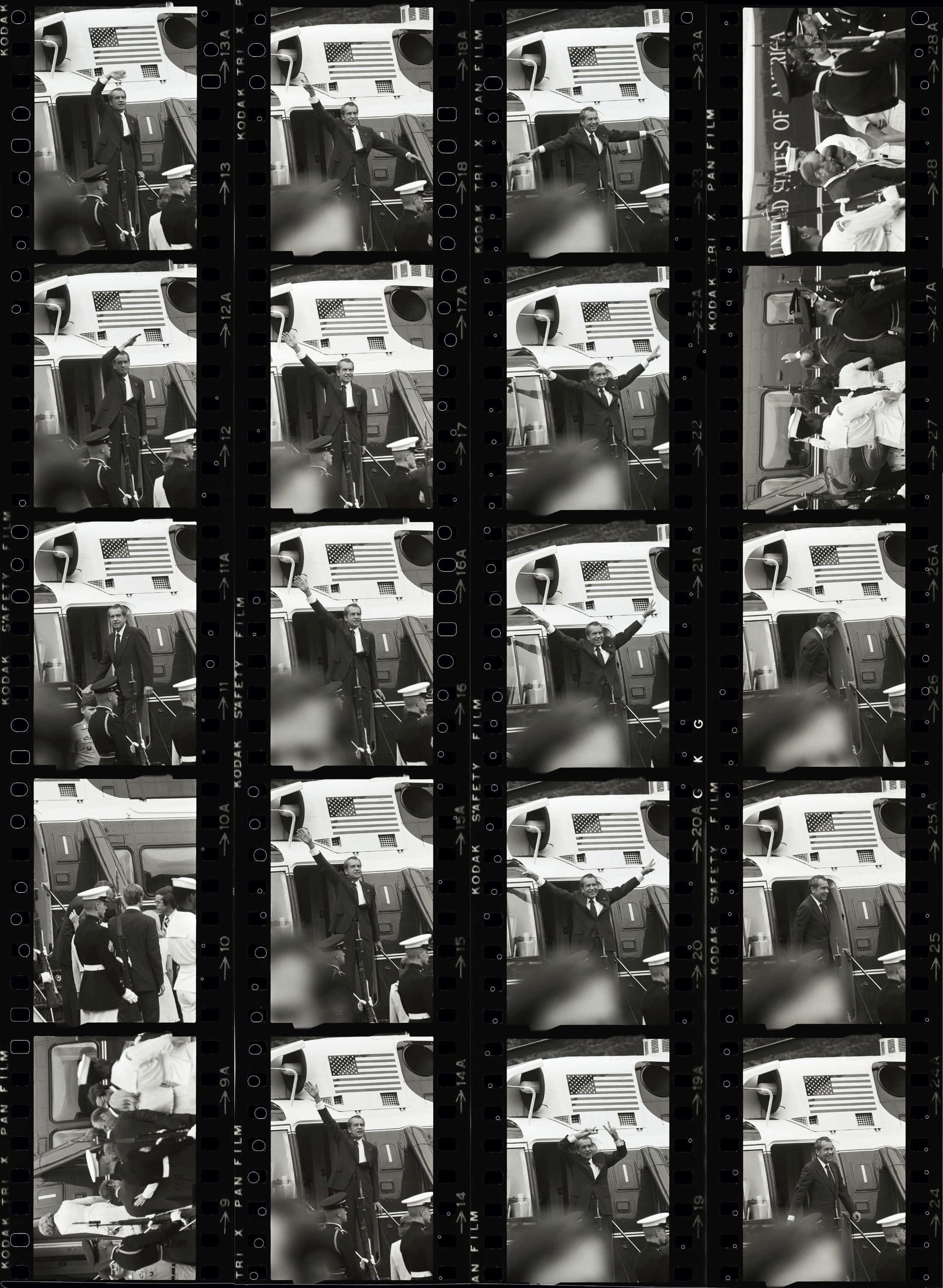

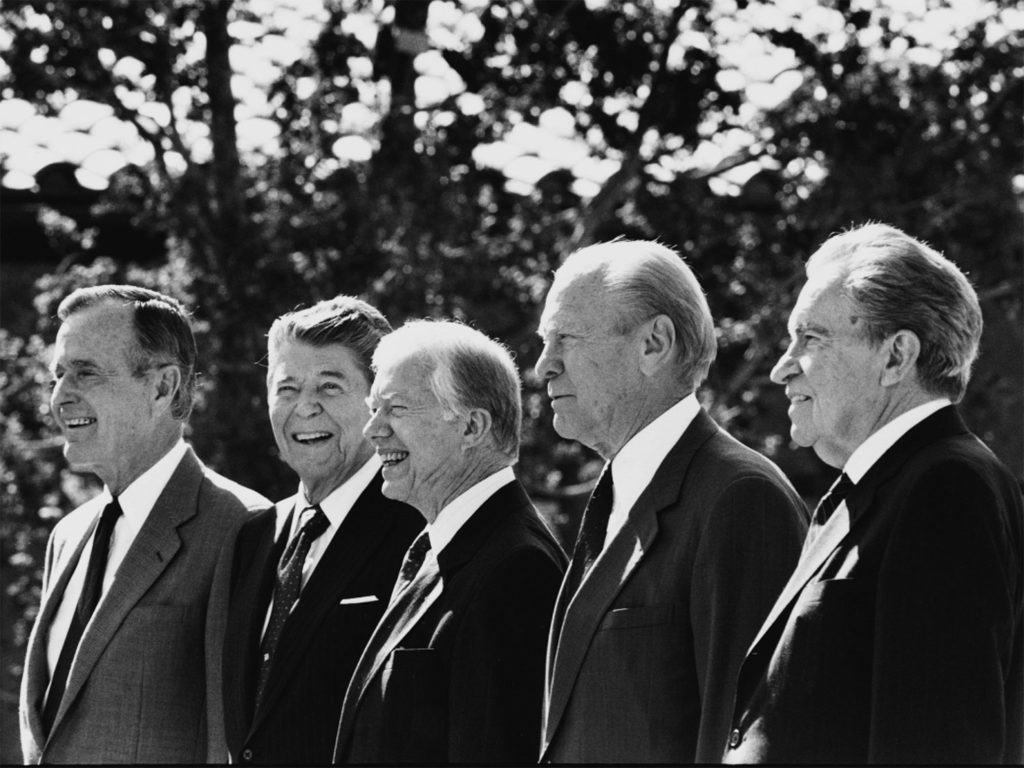

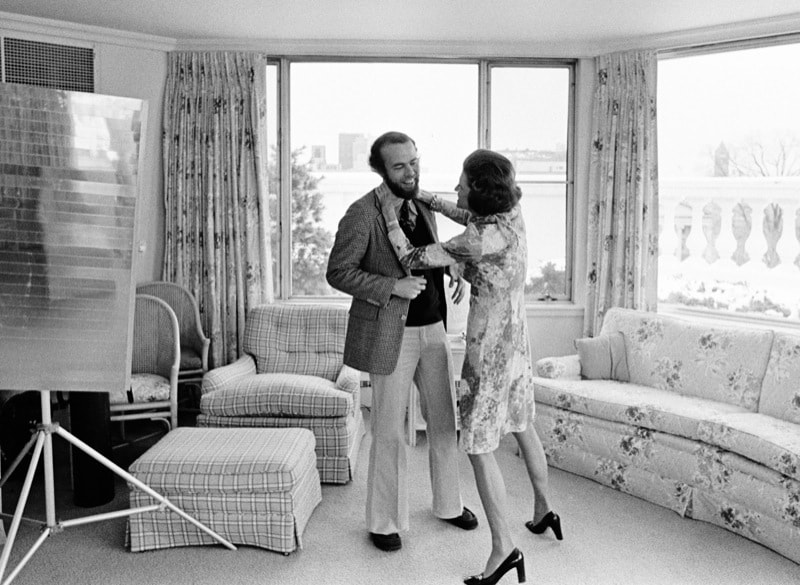

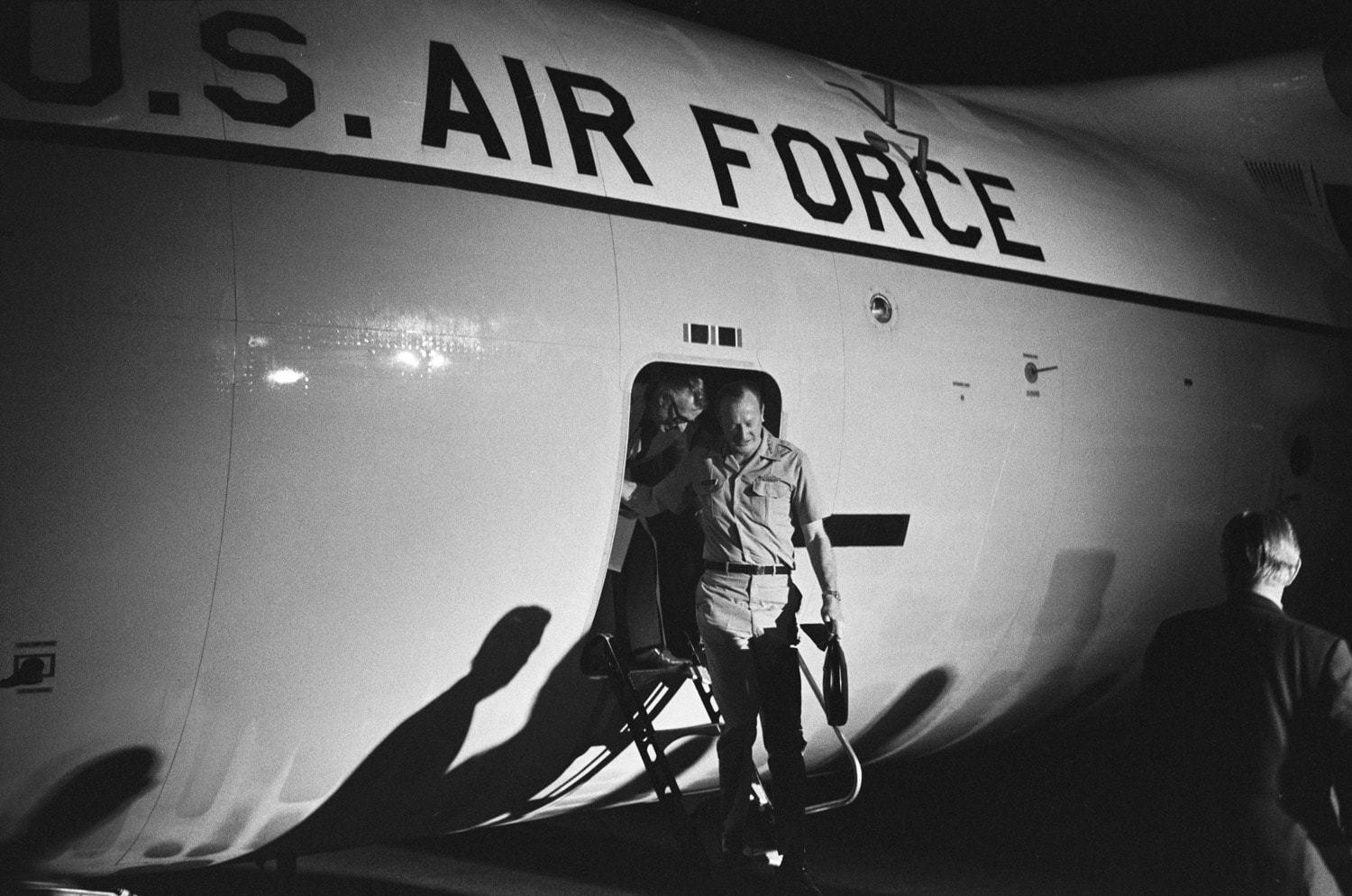

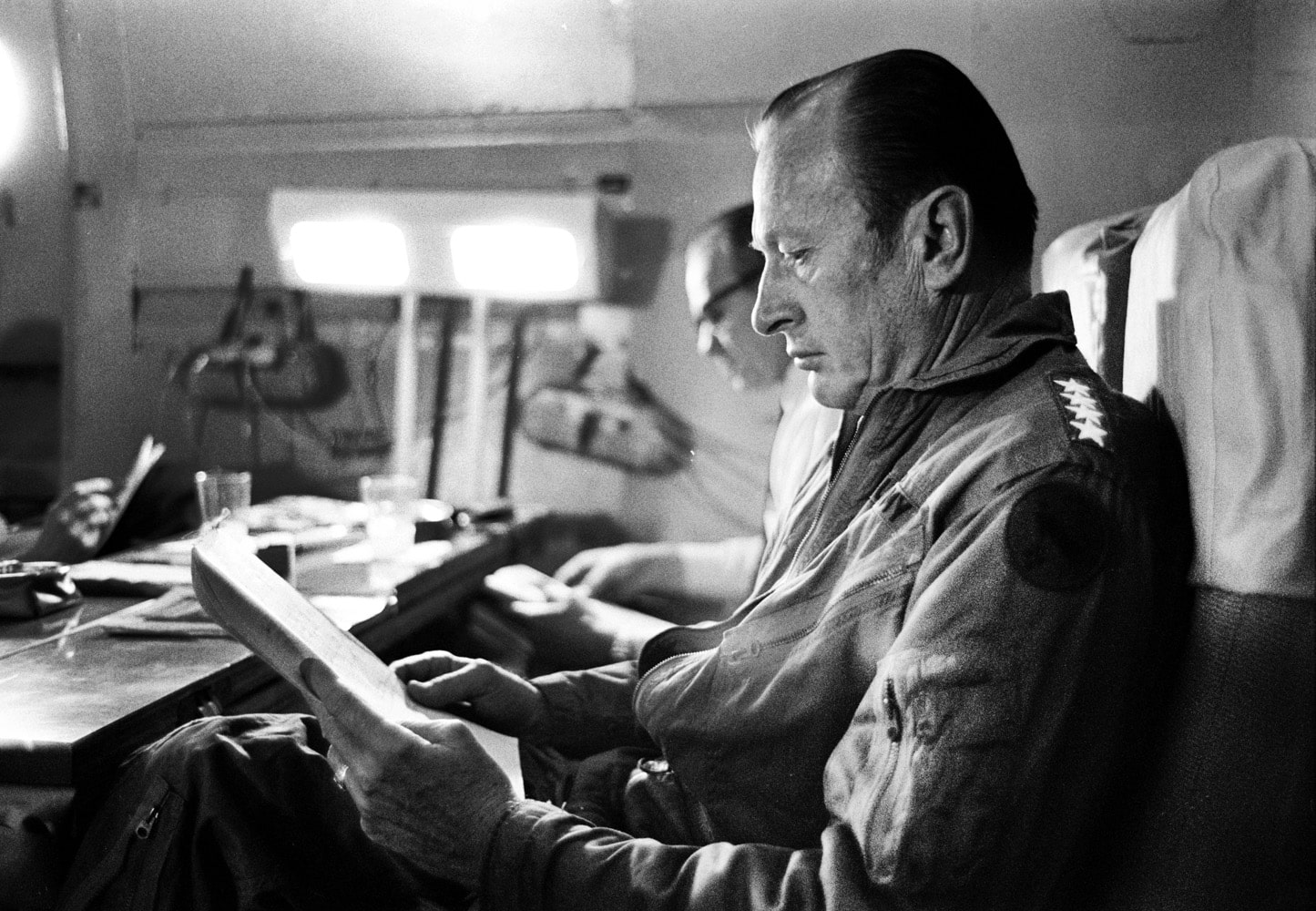

We got to know each other better on a journey from Washington DC to Vietnam and back on a C-141 cargo plane in 1975. 24 hours over and 24 back with plenty of excitement in between. The trip was a sensitive mission ordered by President Gerald Ford to see if anything could be done to stem the tide of the advancing North Vietnamese Army into the South. Weyand was the right guy for the job. He had served several tours of duty in Vietnam and knew the place well.

During one of those tours Weyand was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for extraordinary heroism on two occasions while commanding the 25th Infantry Division. On January 8, 1967 after one of his companies became pinned down by intense Viet Cong fire and surrounded, he directed his helicopter pilot to take him there. The DSC citation says, that Weyand “dauntlessly walked around the treacherous perimeter, comforting the casualties and encouraging the beleaguered defenders. His presence on the battlefield was a source of boundless inspiration and enabled his men to hold out until relief arrived.” Less than a month later he helped locate a two-vehicle patrol that had strayed into enemy territory. Braving enemy fire he landed in front of them, turned them back towards safety, and undoubtedly saved their lives. All in a day’s work for Fred Weyand.

On the flight over to Vietnam we talked about people we had known in the war. One of them, Brigadier General Jim Hollingsworth, had performed similar acts of heroism in 1966 and 67. He knew Holly well, and said admiringly, “That guy was a piece of work!” “Look who’s talking.” I told him. Those guys were true warriors.

General Weyand’s military instincts also helped save Saigon during the Tet Offensive in 1968. A correspondent wrote that, “Weyand got the feeling that something bad was coming right in our own backyard." He convinced a reluctant General William Westmorland to deploy troops in and around Saigon. His prescient action dealt the North Vietnamese a major military defeat and saved the South Vietnamese capital. Weyand knew, however, that the success on the battlefield was offset by the anti-war sentiment back in the U.S., that it took more than military action to win a war. He strongly believed that you needed the American people backing the effort. Even before Tet he privately told people that he didn’t see a good outcome in Vietnam.

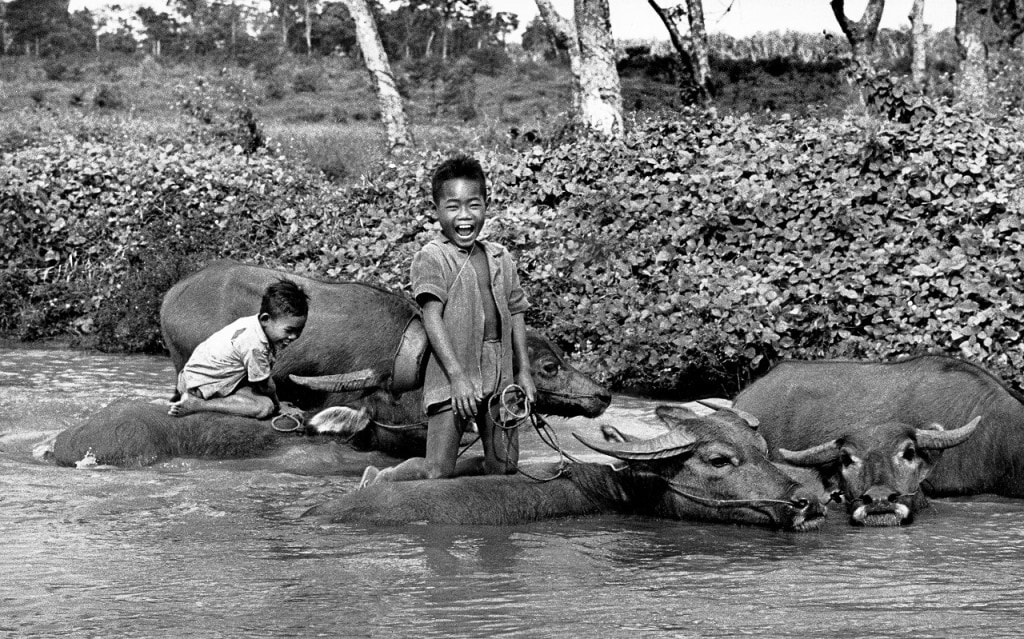

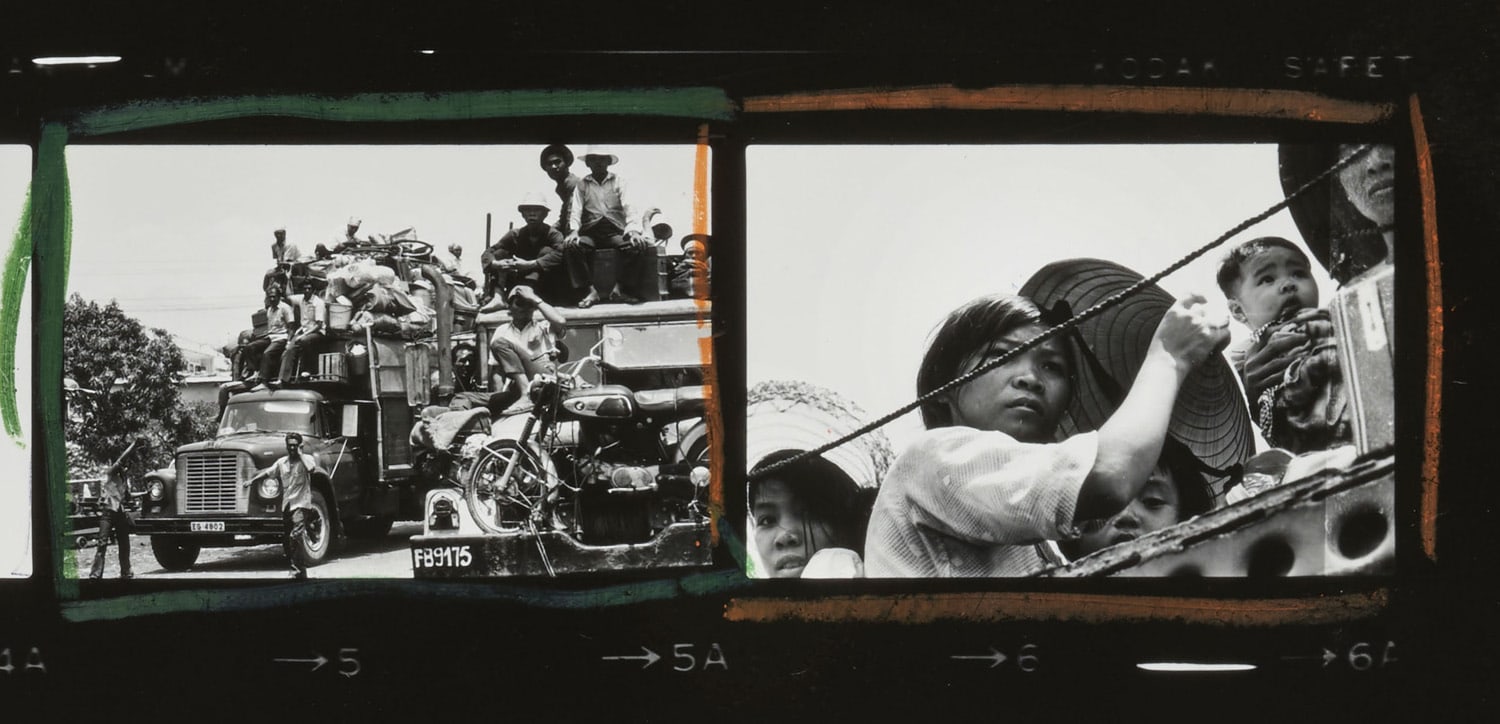

When we landed in Saigon, Weyand went off for briefings on the deteriorating situation. I left his group to make side trips up north to Nha Trang, then over to Phnom Penh, Cambodia. It was chaotic. The night I got to Nha Trang the city was evacuated in front of a North Vietnamese attack. My helicopter took fire from fleeing South Vietnamese troops crowded aboard ships in Cam Ranh Bay. Phnom Penh was worse. The Cambodian capital was surrounded by Khmer Rouge troops. The airport was taking constant fire. Things looked bad.

I made it back to Saigon in time for Weyand’s meeting with South Vietnamese President Thieu. Weyand assured Thieu of Ford’s commitment to him. He laid out some options, but it appeared to me that Thieu was skeptical.

On the flight back to the states I told Gen. Weyand what I had experienced, and it added to his pessimism. We discussed the report he was going to deliver to President Ford. I was pretty sure it wasn’t going to be a hit.

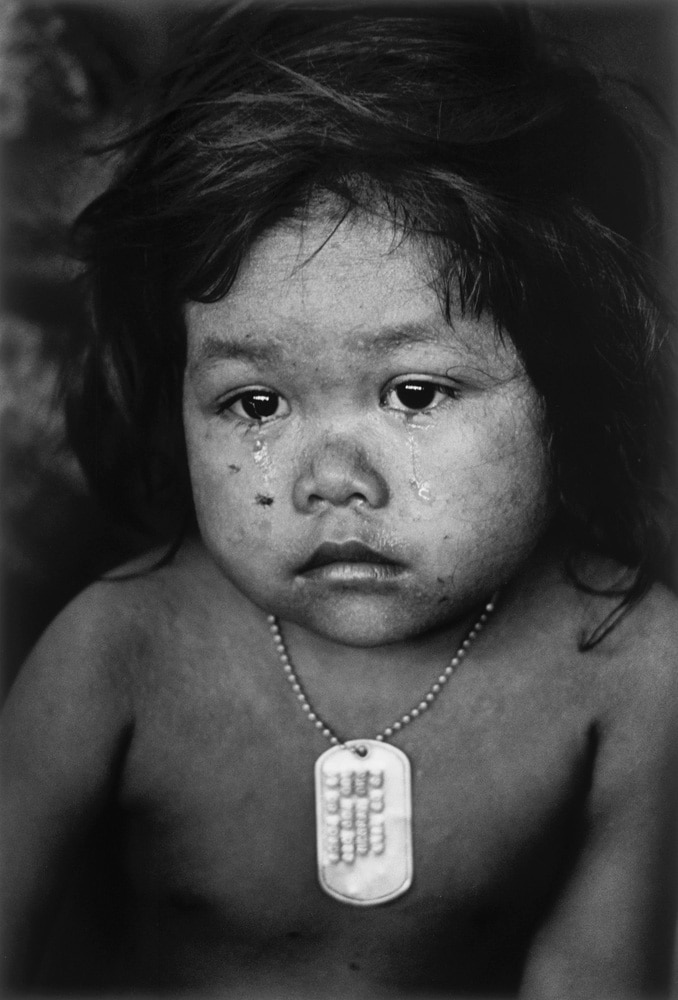

General Weyand gave President Ford his unvarnished opinion. He told him that an infusion of aid to replenish military supplies might help, and at the very least would show public support. He ominously added that the government of South Vietnam was on the brink of military defeat. He also told Ford that the US should plan for a “mass evacuation of some 6,000 American citizens and tens of thousands of South Vietnamese and Third Country Nationals . . .”

There it was. General speaks truth to power. Power didn’t like the message, but believed the messenger.

Saigon fell less than a month later, an event that deeply saddened but didn’t surprise General Weyand.

In an interview with Col. Harry Summers in 1988, Weyand said, “What particularly haunts me, what I think is one of the saddest legacies of the Vietnam War, is the cruel misperception that the American fighting men there did not measure up to their predecessors in World War II and Korea. Nothing could be further from the truth.” And the general knew that firsthand, he had served with distinction in all three of those wars.

It is such a wonderful tribute to General Frederick Weyand to have this beautifully designed U.S. Army Pacific Headquarters building named after him. Knowing Fred, however, I think he would have been a wee bit uncomfortable with all this attention!

Nancy told me that her dad and mom retired in the islands because they loved the Hawaiian spirit. That spirit, and Fred Weyand’s, will always be with you whenever you enter this magnificent place.

Aloha, Fred.