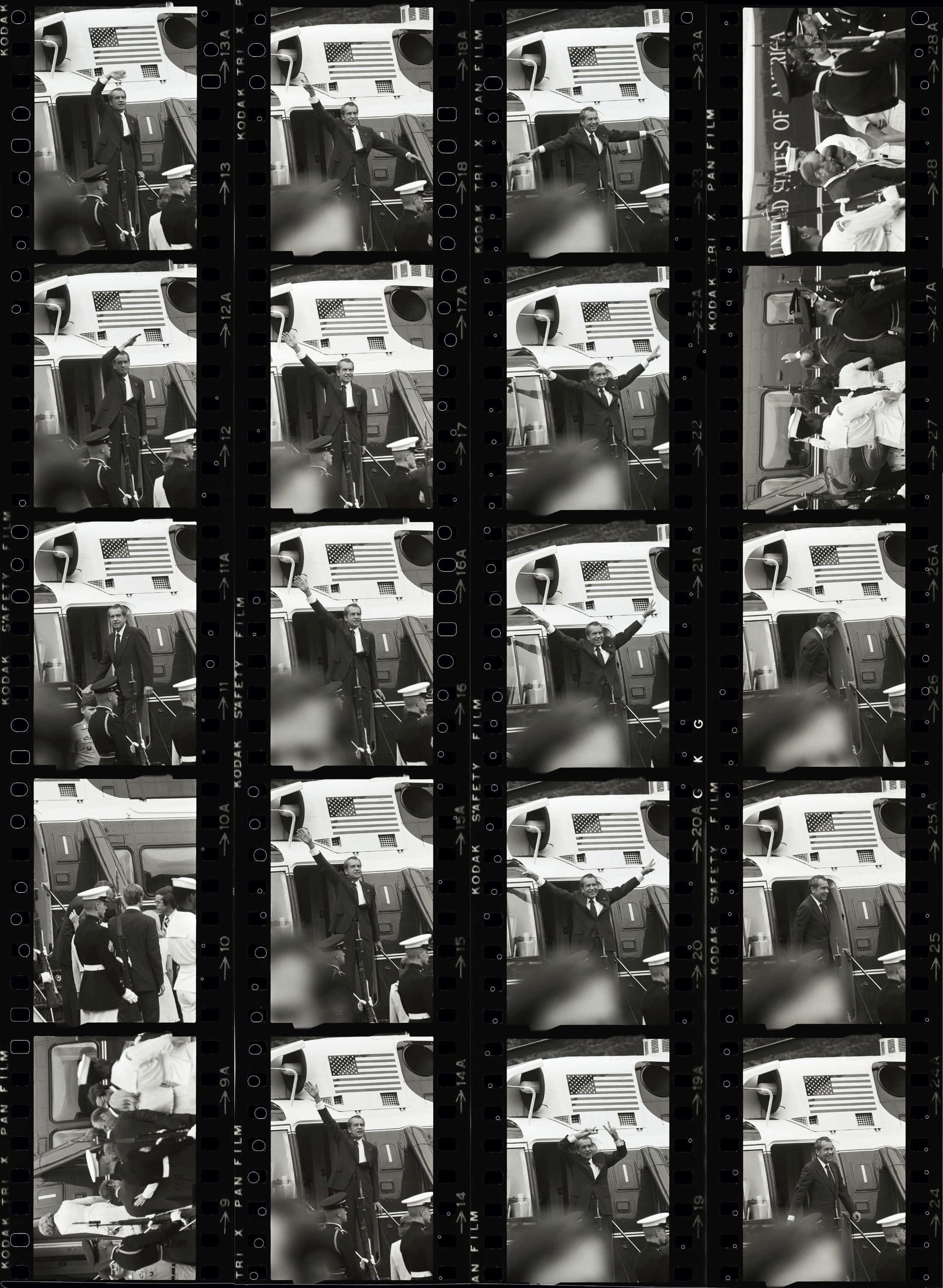

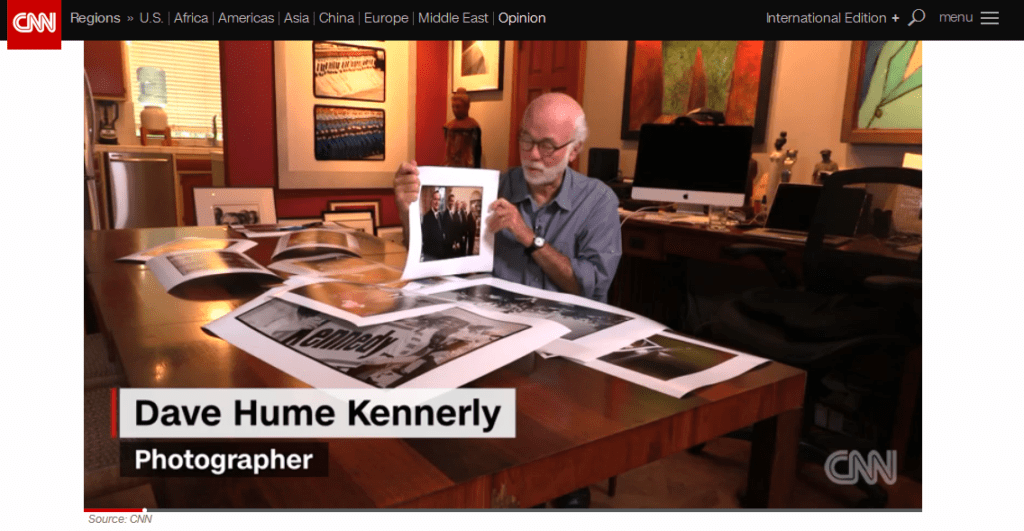

Progress Report from the Kennerly Archive

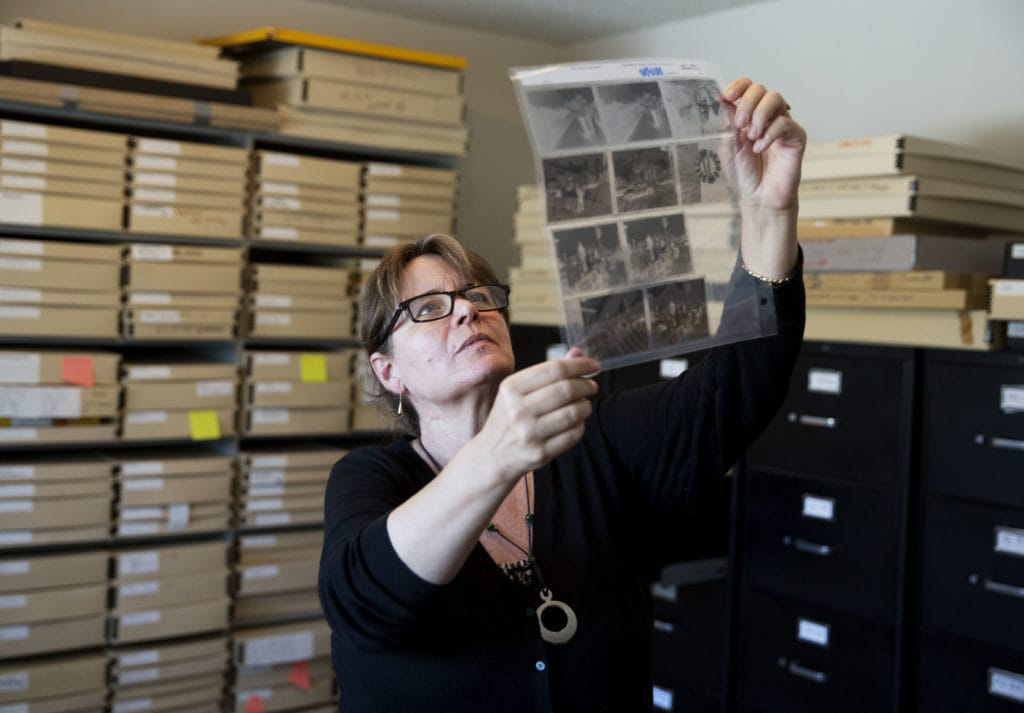

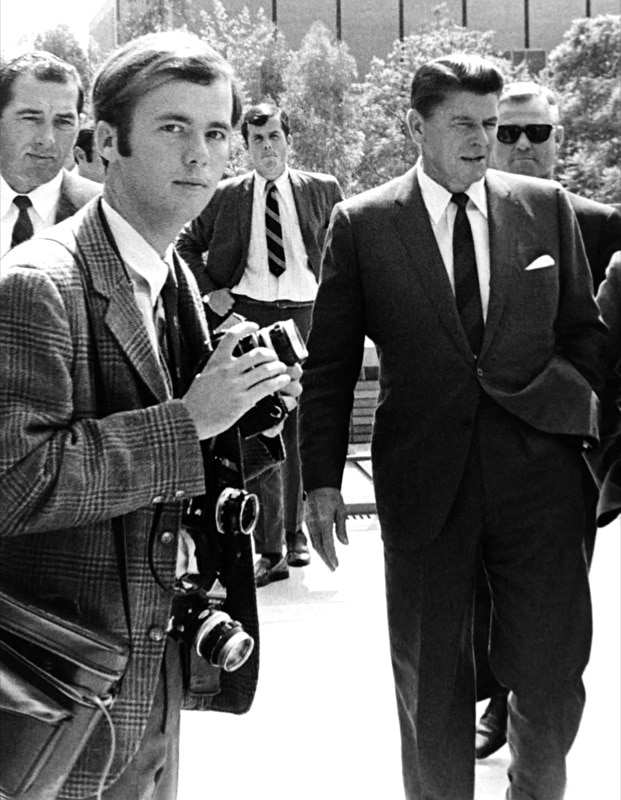

We are so fortunate to have been able to bring Randa Cardwell on to the Kennerly Archive team last year – a team that now numbers three, counting Rebecca, Randa and myself. Randa graduated from UCLA with a Masters in Library and Information Sciences, with a subspecialty in digital and photos! She has a fantastic instinct for pictures and doesn’t seem the least phased by the size of my monster collection. Her skills and expertise have pushed the Kennerly Archive Project into overdrive and her judgement has allowed us to effectively sift through piles to locate and protect the gems.

Thank you, Randa!