I’d been covering the 2016 presidential campaign for CNN since the year before, but when I showed up to photograph an appearance by Hillary Clinton at St. Anselm College in New Hampshire, I hadn’t seen her in a couple of months.

The first time I photographed her was when she was a young lawyer working on the Nixon impeachment hearings in the House Judiciary Committee in 1974. I’d gotten to know her pretty well since then, even made a trip with her in 1998 where she visited Russia and several other countries in the area. So when Sec. Clinton saw me at the St. Anselm rally she came over to say a cheery hello. I asked how she was doing, and she leaned over and said, “I wish the election was tomorrow.” Had it been the next day she would have won, but two weeks and a day later, on Nov. 8, Donald Trump was elected president.

What Mrs. Clinton and nobody else knew at that moment was that in reality she would lose the election four days later on October 28 when Director of the FBI James Comey reopened the investigation into her emails. It was a shocking and unpleasant twist, particularly being so close to a presidential election. Clinton’s use of a private email server during her time as Secretary of State had been a campaign issue, but earlier in July the FBI decided not to recommend criminal charges against her, so as far as the campaign was concerned it was case closed. Until suddenly it wasn’t.

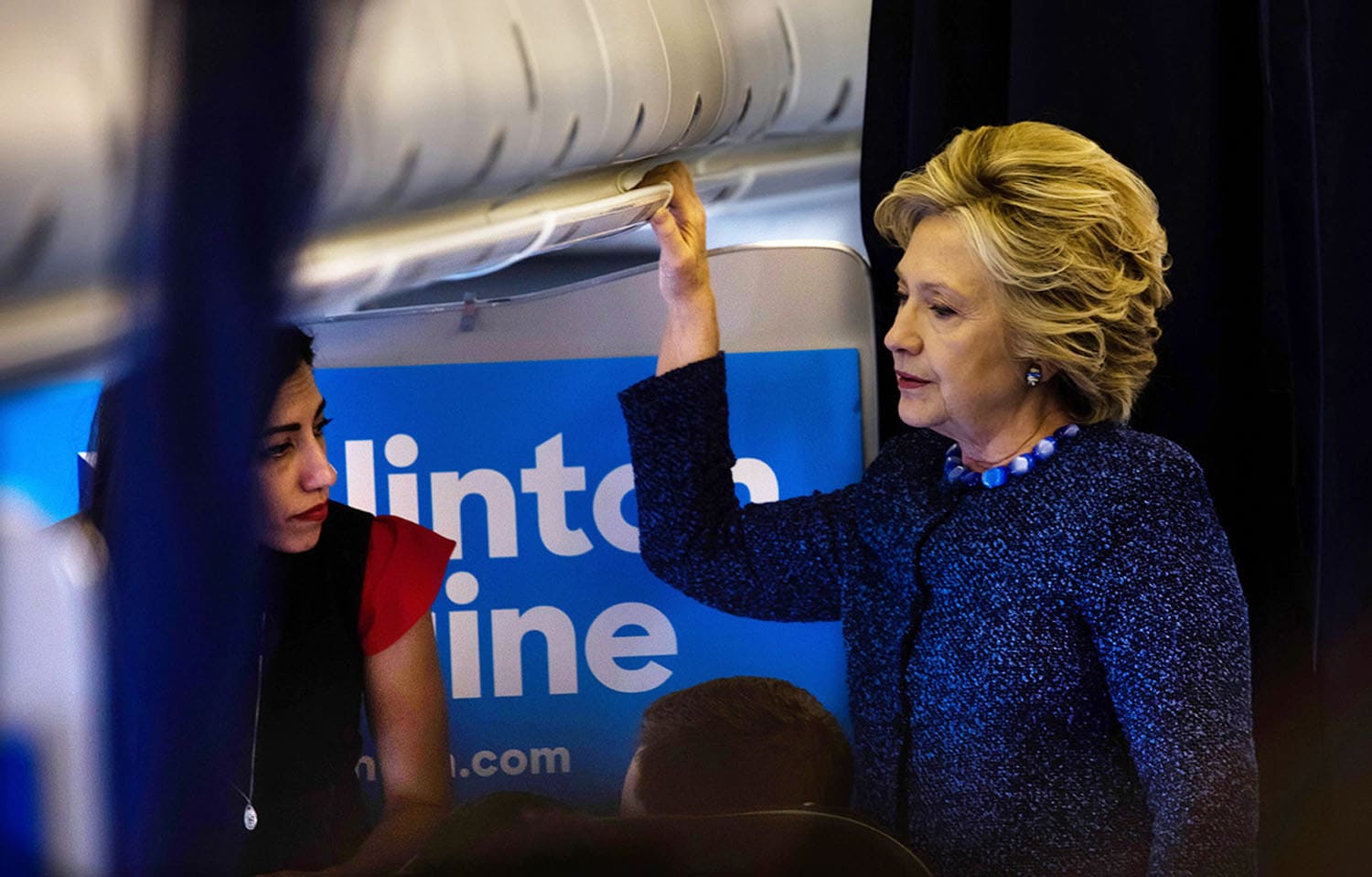

On that day I was in the back of Sec. Clinton’s campaign plane traveling from New York to Cedar Rapids, Iowa with her. During the flight word reached us about the new investigation. Mrs. Clinton had no advance warning that the FBI would be doing that. Comey had informed Congress, but not her.

Clinton's top campaign staffers, including her close aide Huma Abedin, had to immediately figure out what to do about the earthshaking revelation. At that point it was only eleven days until the election. They learned later that the emails in question were part of an investigation into Abedin's estranged husband, former Congressman Anthony Weiner.

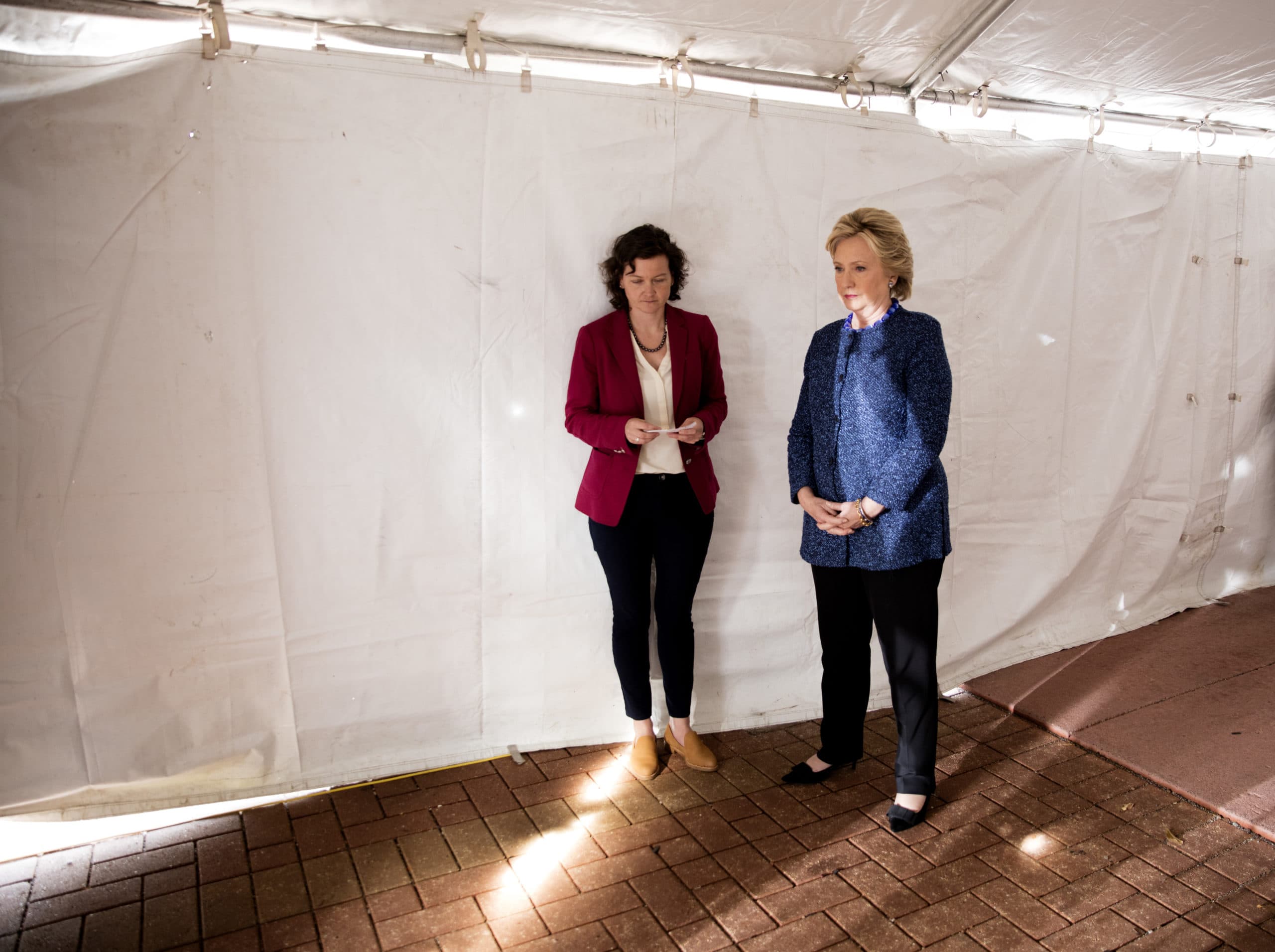

After landing in Iowa, we waited for almost 45 minutes for Sec. Clinton to exit her plane. It was clear there was an emergency meeting going on about how to deal with this unexpected crisis. The press shouted questions at her when she finally deplaned, but she ducked into her car without saying a word, and headed to her scheduled rally. I was with a pensive Hillary Clinton backstage as she waited to enter the event. Nobody was talking about the FBI.

One poignant and ironic photo I made at her second campaign event in Des Moines was a shot of her striding down the catwalk with a large “Madam Potus” sign in the crowd. The rally wasn’t the story, although like the first one she got through it as if everything was ok. The press conference afterwards was where the news was made. The hastily put together presser was held in the school’s choir room. Clinton appeared grim but resolute. She said, “We don't know what to believe. And I'm sure there will be even more rumors . . . it is incumbent upon the FBI to tell us what they're talking about . . . We are 11 days out from perhaps the most important national election in our lifetimes. Voting is already underway in our country . . . so the American people deserve to get the full and complete facts immediately. [Comey] himself has said he doesn’t know whether emails referenced in his letter are significant or not. I’m confident, whatever they are, will not change the conclusion reached in July.”

For election night Hillary Clinton's campaign had reserved the huge Javits Convention Center for what they thought would be a monumental celebration of the first woman in American history to become president. A few blocks away, in the smaller New York Hilton ballroom that had been contracted by a campaign who thought they would lose, I was there to document a stunned-looking Donald Trump as he declared victory. But he had really won eleven days earlier.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.