I recently received a nice note from Bill Garlinghouse, a retired Navy combat cameraman who wanted to share a story with me about how a passage that he read in my book Shooter in the early eighties helped him out on his first foray into combat.

I reprint this with his permission, and follow it up with the pertinent excerpt from my book.

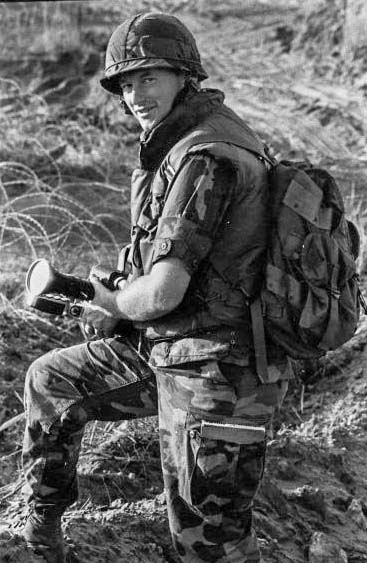

“In the 80s, I was an enlisted Navy photographer with a specialty in motion picture. In '83 I was assigned to Navy Combat Camera. At that point, none of us were old enough to have seen combat. Our experience was documenting exercises.

During those early days in Combat Camera, someone brought a copy of your book "Shooter" to work. We'd often read paragraphs we liked out loud. I was struck by the paragraph in which you said to be in the third lift in during a helo assault. I read that out loud to my teammates.

That year I got a midnight call from my commanding officer to get into work, and to bring my gear. It turned out we were going to document the helo assault of the island country of Grenada in the Caribbean. (editor’s note: The U.S. attack came over concern that 600 American medical students living there might be taken hostage by the hostile government in power).

The morning of the assault, I took my team down to the helo deck on the USS Guam. I told the Marine LT running the show that we were there to cover the action. He said he'd put us on the last helo in. I looked him in the eye and said "No sir. We need to be in the third helo in." He asked why, and I explained that by the time that helo lands the perimeter is set, and we can point up and catch the rest of the helos coming in.

He said 'Roger that!'

My team landed in the soccer field. We followed the Marines out. I found a spot where I could see the ramps of all the helos on the ground, lined up and disgorging Marines. I aimed my Arriflex up at the next helo coming in, started rolling, and followed it down into that preplanned final composition in which marines ran off the ramps of the helos that had already landed, and still more ran right in front of me!

All our film of that day was put on a helo to an aircraft carrier where an F14 took it to DC. I never saw any of it until a few years later when 60 Minutes did a piece on lessons learned from that action. I watched the show looking for something my team may have shot, and saw nothing.

Until they ran the show's closing credits over it!

There it was! The shot I considered to be my legacy shot if I ever had one. The one I had never seen except in my viewfinder and many times in my mind's eye.

The one I have you to thank for!

Your book sits in a place of honor on my bookshelf. The page with your guidance to me bookmarked!

Thank you for your service sir!

V/r LT W.J. Garlinghouse, USN (Ret)”

No, thank you Bill.

Here’s the piece from Shooter that he referred to. Just glad the advice that was passed along to me before I went on my first combat mission in Vietnam didn’t get Bill whacked!

Charlie Alpha. To anyone who's ever been to Vietnam those letters mean “combat assault” by helicopter. There are two kinds of CAs. The easy kind goes into a cold landing zone, or LZ; the other kind goes into a hot LZ. Neither has anything to do with temperature. A CA into a hot LZ means that the bad guys are shooting at your Huey as it lands. A company-sized CA usually involved four choppers per platoon, six soldier to a helo. To land a full company, sixteen helicopters transport one hundred men in four separate lifts. The advice given me by veteran newsmen was to always go in on the third lift. By that time fifty soldiers were already down, securing the LZ, and another twenty-five would be coming in right behind you . . . also better for picture taking as they jumped of the helos and scrambled for cover.

My first clue as to the kind of LZ we were approaching came when I noticed that the crackle of small arms fire was louder than the rotor blades of the chopper. It was a hot one. I soon found myself running at or half-crawling away from the LZ towards soldiers who were returning the enemy fire. (That “third lift” advice wasn’t making me feel particularly good). The very idea of being in the middle of a firefight had my heart beating faster than a hummingbird's. My breath was coming in quick, shallow gulps. In other words, I was scared shitless. The area was a twisted mass of mangled tree trunks, upended boulders, and smoking holes left by incoming artillery rounds. I noticed a young private wedged between two rocks. He had been hit in the face and was in a bad way. Everyone else was involved in keeping the enemy at bay, so I took a medical compress from the band of his helmet and tried to stop the bleeding.

My combat attire, which included a green medical cravat, camouflaged jungle fatigues, the small backpack that all GIs carried, and a brown fedora instead of a helmet, made it clear to him that I was not military. My attire, coupled with my beard and cameras, distinctly separated me from the regular GIs. "Just here taking a few snaps," I responded. "Do you have to be here?" he asked incredulously. "Not really," I replied. He looked at me and shook his head. "If I didn't have to, I wouldn't even be here."

When I got back to Saigon I told a couple of colleagues about my first firefight, and about the wounded soldier. One of them asked if I'd taken any pictures of the poor guy. "After I fixed him up," I replied. "You asshole," he said. "Take the picture, then put on the compress."

So it goes in covering a war. I think the better advice is to avoid any lift into action if possible!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.